by Jean Marie Carey | 16 May 2017 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

This post goes with a book review of the exhibition catalogue Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim (2017) for Museum Bookstore which is posted here and also follows in a slightly different form below.

It has been one of life’s great pleasures to see Franz Marc’s Die gelbe Kuh many times over the years at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Every time I get the same huge surge of joy as the first, and I think other people feel the same way. When the painting is where it lives normally, in the Thannhauser wing, you can sit on a bench in the gallery and watch people come in, weaving their way through some much smaller woodcuts and decorated books, and then turn the corner to be met by this enormous colourful and cheerful painting. Always a lot of oohs and ahhs and delighted small children.

§ § §

People admiring Franz Marc’s Stallungen (1913, l) and Die gelbe Kuh (1911) at the Guggenheim.

Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim

Edited and introduced by Megan Fontanella with chapters by Vivien Greene, Jeffrey Weiss, Susan Thompson, Tracey Bashkoff, Lauren Hinkson, and Susan Davidson and published by Guggenheim Museum Publications, this catalogue accompanies the eponymous exhibition held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City, 10 February-6 September 2017; 312 pages with color reproductions of all the paintings and sculptures from the exhibition plus archival photographs, illustrations, letters, and newspaper and magazine notices.

The “modernization” of European art around 1900 is usually associated with the evolution of line, color, and figuration toward abstraction, as manifested by Expressionism and Futurism. The fact that art collectors and dealers played an important role in codifying what we think of now as Modernism is brought to full light in the catalogue Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim, produced to coincide with the exhibition of the same name.

In fact the catalogue seems, at least at first glance, intent upon driving home the idea that art is a business, opening with the normally blank flyleaf emblazoned with corporate logos and an unprecedented “Sponsor Statement” by Francesca Lavazza, heir to the Lavazza coffee brand, the underwriter of the exhibition. However the scholarly contents are innovatively presented and well-researched, with five sections devoted to each of the “visionaries” (in this case being the collectors, not the artists), paired with a focus on one of the museum’s key acquisitions. An opening essay by the Guggenheim’s curator of collections and provenance, Megan Fontanella, introduces the scope of the exhibition and the historical circumstances that allowed American entrepreneur Solomon Robert Guggenheim to decide in the 1920s, after five decades dominating the U.S. mining industry, to become the world’s foremost collector and exhibitor of what became dubbed “non-objective” art. (42) As in the rest of the book, the introduction offers wisely-selected and superbly reproduced works from both the immediate exhibition and from other sources.

Of great interest are photos of the assorted collectors and dealers in domestic settings, surrounded by their objets, which are very revealing, perhaps beyond what is intended by their inclusion in a book that is an official history of the Guggenheim. It is impossible, for example, not to be vexed by the careless profligacy of Peggy Guggenheim, niece of Solomon and founder of the Guggenheim Collection Venice. She is shown on the terrace of an Île Saint-Louis flat, wearing pearls and sipping an espresso as the Nazi-occupied Paris of the 1940s falls away across the river, Constantin Brancusi’s Maiastra (1912) set perilously on the parapet beside her. (254)

In fact the catalogue is an outstanding exercise for those willing to read between its restrained lines. Taken this way, an excellent contemporized portrait of the Guggenheim’s co-founder and first director, Hilla Rebay, emerges. Fontanella and Susan Thompson dispense with the “female hysteria” characterization of Rebay as the occult-obsessed lover of painter Rudolf Bauer to focus on her acumen as a businesswoman and strategic positioning as a collage artist. Thompson shows Rebay’s collages – figurative portraits for the most part, more like mosaics made with bits of paper than Hanna Höch’s more associative and confrontational critiques of Weimar culture – as a distinct oeuvre outside the canonical avant-garde’s concentration on sculpture and painting.

Equally calculating and less sympathetic is Rebay’s outsize ambition as Guggenheim’s chief advisor and deal-maker. Fontanella reports:

Rebay […] did attend the notorious Entartete Kunst show in Munich in August 1937, fresh from the June establishment of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. The foundation would make important purchases from the ensuing German-government-sponsored degenerate art sales: [Wassily] Kandinsky’s Der blaue Berg (1908-09) and Einige Kreise (1926), and [Paul] Klee’s Tanze Du Ungeheuer zu meinem sanften Lied (1922) were among the works that entered its holdings this way in 1939 – works that might have been destroyed. (30)

…Or works that might have been returned to their rightful owners.

(more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 7 Jan 2017 | Art History, August Macke, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism

Whatever happens in the future, my time in Münster will be the happiest I can ever remember. I was there for several weeks and finally had a substantial Paradies mural Franz Marc and August Macke made together in Macke’s upstairs atelier in Bonn in 1912.

Whatever happens in the future, my time in Münster will be the happiest I can ever remember. I was there for several weeks and finally had a substantial Paradies mural Franz Marc and August Macke made together in Macke’s upstairs atelier in Bonn in 1912.

The mural was moved to Münster’s LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur in 1984. In a quiet room away from the museum’s main traffic areas, the mural is now the altar of a shrine to Macke and his relationship with his wife Elizabeth but also with Marc, phrases from his many letters to August decorating the blue walls.

The Hanseatic light of the west is stunning and soothing, like a house you’ve lived in your entire life – something almost no one does anymore that seems like a real memory.

by Jean Marie Carey | 28 Jul 2016 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

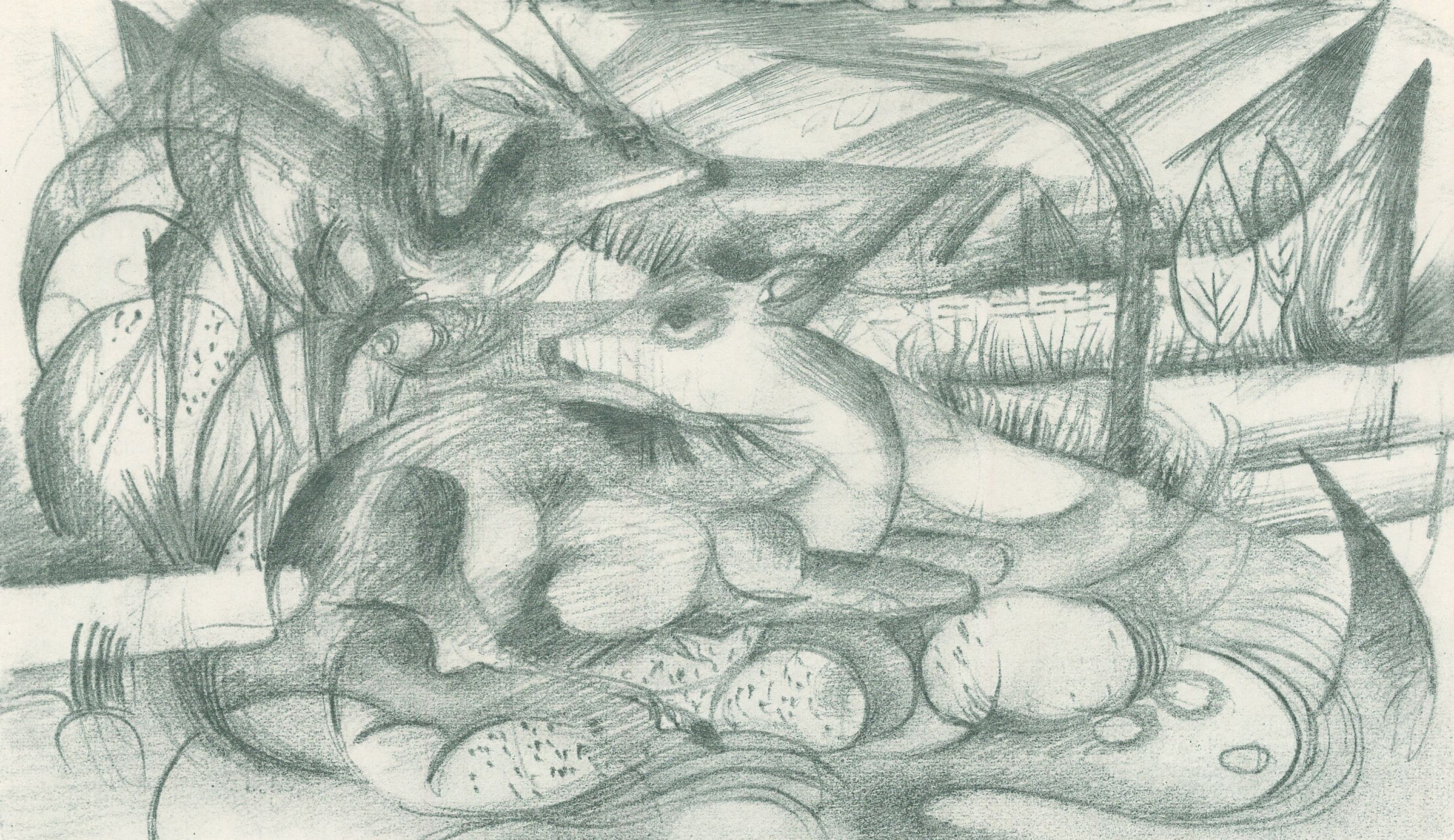

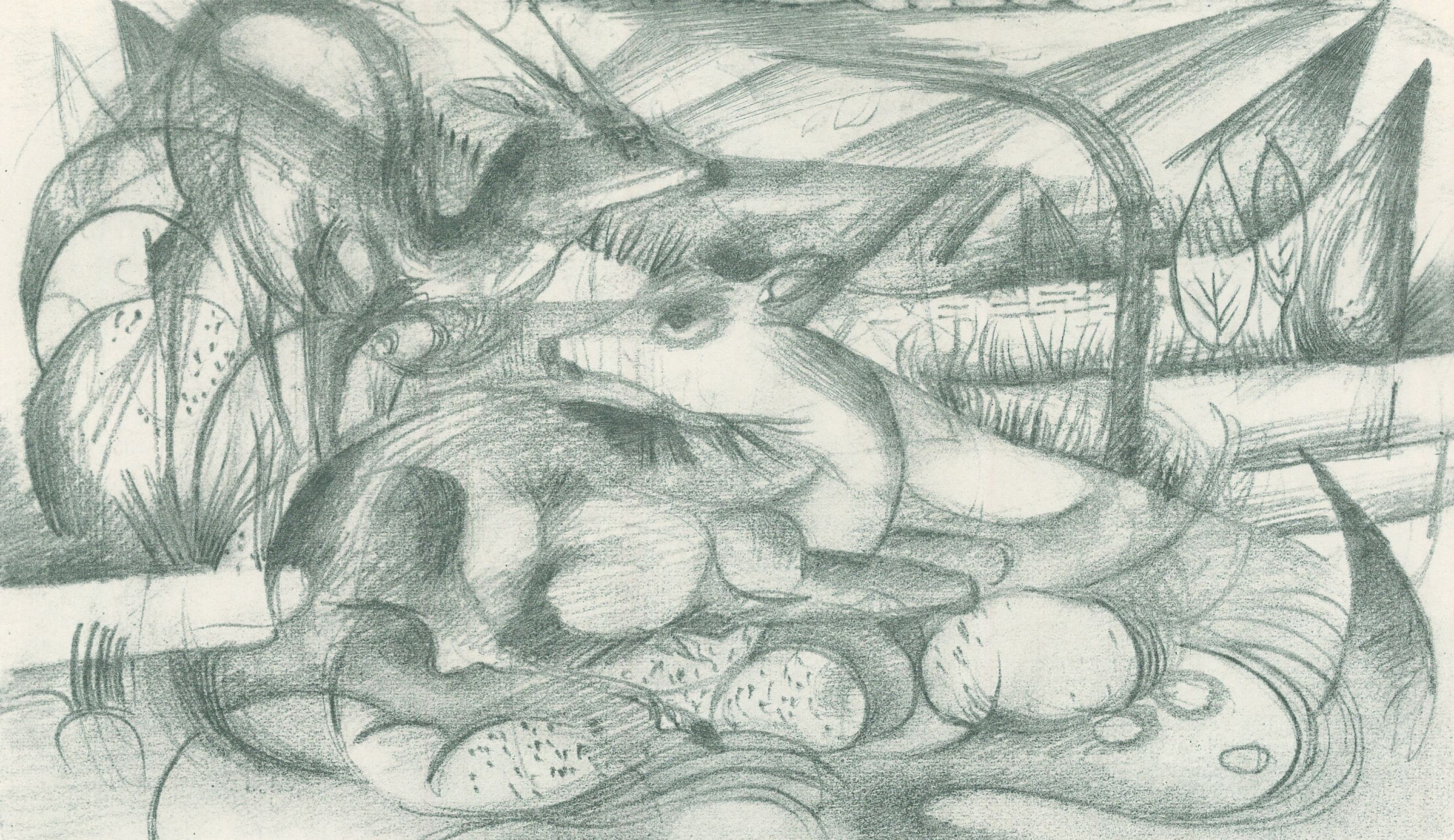

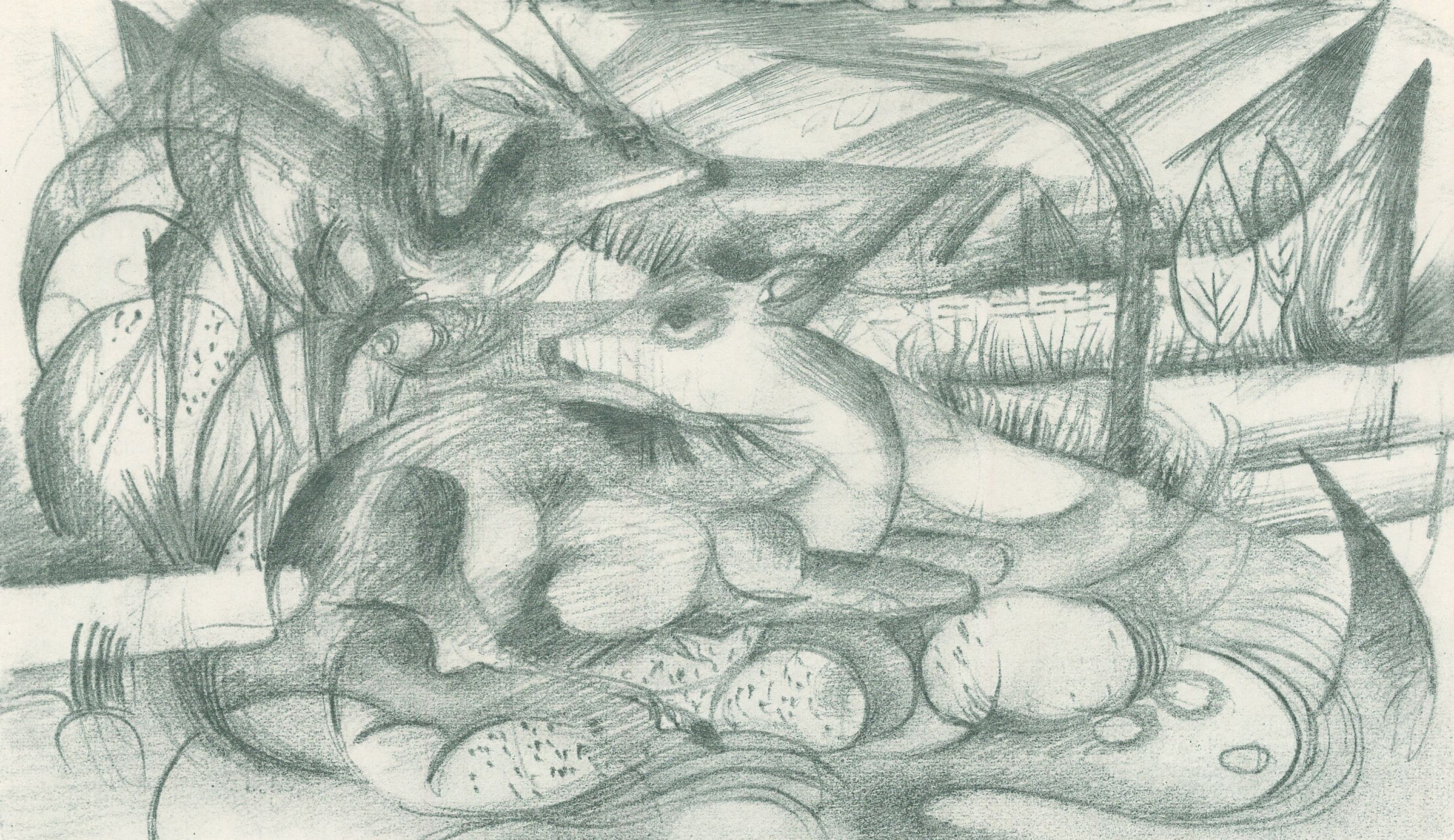

Franz Marc’s mysterious nude in a landscape from around 1911.

In clear contrast to the well-planned execution of the grazing horses on its front, the verso of Weidende Pferde IV is wild, mysterious, and haunting, and provides an intimate look at Franz Marc’s more intuitive approach to color and form.

Though the composition is partially obscured, the underlying motifs are clear enough.

Shown is a reclining female nude in a dimly lighted landscape under a deep blue sky. The figure rests on her back, her right leg is bent. Her head with long and flowing red hair is slightly tilted to the right; her arms clasped behind her. This figure is somewhat characteristic for Marc in terms of the visible hatching and decorated, colorful outlines. The left of the picture area seems to indicate another figure whose gender and position we can only guess at. The middle of the picture consists of a dramatic, deeply-hued landscape, which in turn is what the reclining nude in the foreground would be part of and also looking at. Though Marc often painted nude figures relaxing outside, this painting does not seem to correspond to another finished work.

Weidende Pferde IV, 1911

Weidende Pferde IV is also a stunning picture when considered in terms of Marc’s efforts to produce it: Three red horses with purple mane prance against a lemon-yellow sky and a deep blue rock formation. Marc had devoted a lot of time to developing the arrangement of the horses’ bodies in this formation. Marc had been preoccupied, and had made a difficult and lengthy process of, how exactly to balance the shapes and colors of the horses in the overall composition.

Weidende Pferde IV is the star of the second part of the exhibition trilogy “Franz Marc: Zwischen Utopie und Apokalypse,” presented by the Franz Marc Museum in Kochel on the 100th anniversary of the death year of the painter. This is one of just a few paintings that Marc saw hung in a museum himself, following its creation in 1911 and first display at the Thannhauser’s Galerie Moderne in Munich

The same year the collector Karl Ernst Osthaus purchased Weidende Pferde IV for the Folkwang Museum’s first incarnation in Hagen. The painting sold for 750 marks, as Marc triumphantly informed his brother Paul on 3 December 1911.

Marc had been constantly busy with live horses during his years in Kochel and Sindelsdorf (“Pferde auf Bergeshöh gegen die Luft stehend”), and he studied them in detail as he drew, printed and painted them.

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1909

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1910

-

-

Franz Marc, c. 1910

The day before Alexej Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin and Adolf Erbslöh first visited Marc in Sindelsdorf on 3 February 1911, he wrote to Maria Marc who had at this time had left Bavaria to stay with her parents in Berlin, “Ich habe noch ein großes Bild mit 3 Pferden in der Landschaft, ganz farbig von einer Ecke zur anderen, angefangen, die Pferde im Dreieck aufgestellt. Die Farben sind schwer zu beschreiben. Im Terrain reiner Zinnober neben reinem Kadmium und Kobaltblau, tiefem Grün und Karminrot, die Pferde gelbbraun bis violett.”

The visitors loved the paintings, and by the day of his 31st birthday on 8 February Marc was a co-chairman of Neue Künstlervereinigung München.

Certainly the powerful painting of the reclining redhead should be regarded as an entirely discrete creation and given a proper name and place in the artist’s catalogue raisonné. It is curious that Harvard University’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, which purchased the painting when it was declared Entartete Kunst in 1937, has not taken the initiative to see that this is done. If only this painting could be permanently repatriated to Kochel, where it belongs.

by Jean Marie Carey | 7 Jun 2015 | Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

Franz Marc, Skizzenbuch aus dem Felde, Skizze 24, 1915

I recently looked harder at Franz Marc’s experiments with poetry. I think you could say that much of Marc’s writing borrows structurally from poetry, and Marc read a lot of poetry, including all of the classics you’d expect, work by people he actually knew, such as Gottfried Benn and Else Lasker-Schüler. He was also interested in French Symbolist Stéphane Mallarmé, particularly Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard of 1897, having extensively annotated a copy of the text; contact with Hugo Ball, who was influenced by Mallarmé’s text/design, probably heightened Marc’s attention.

From 1912 Marc made doodles of lines of the following poem here and there, and of course the last line is what Marc had originally intended to be the title of the painting we know as Tierschicksale (1914). But it was not until 1915 he wrote these phrases down all together in his small portfolio of drawings made in Germany and France, during the war. It’s hard to say what the poem means, especially in the context of the (approximately – some leaves may be lost) 35-page sketchbook’s compact animal images, it is very interesting. A translation is elsewhere but here is the original poem:

“…ein rosafarbner Regen viel [sic] / auf grüne Wiesen. / die Luft war wie grünes Glas. / das Mädchen [sah auf’s] blickte ins Wasser; das Wasser war klar [rein] wie Kristall; da weinte das Mädchen. / die Bäume zeigten ihre Ringe; die Tiere ihre Adern”.

(Abgedruckt in: Klaus Lankheit: Franz Marc: sein Leben und seine Kunst. Köln: DuMont 1976, S. 124.)

by Jean Marie Carey | 6 Apr 2015 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, August Macke, Dogs!, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL

Hund vor der Welt, Franz Marc (1912). Oil on canvas, 118 by 83 centimetres, private collection, Switzerland

I write about this painting a lot – in fact I once, for quite a long time, devoted my academic research solely to this painting – but I realised I don’t often say anything about it in this space. So here is a little excerpt not from my current chapters but from a side project.

§ § §

Franz Marc made an innovative painting – a metaphysical genre portrait of his dog Russi – called Hund vor der Welt in the spring of 1912. The large vertical canvas shows the white hound seated on a hillside, facing the sun and the landscape at an angle across an indeterminate space. We have an account of what Marc had in mind in making this image in particular and Marc’s other thoughts about painting his frequent model.[1] There is also a substantial amount of documentation about Russi, the dog, who, as the artist’s constant companion, was a character who populated the art, photographs, and writing of other people. We even know where Russi was born, how he came as a puppy to live with Marc, and when he died.[2] So despite its slightly whimsical affect, Hund vor der Welt is an image of a real dog about whom much historical information is available. Marc made many paintings in which Russi also appears as a peripheral regular “character;” he leads the way in Im Regen (1912) and leaps after Die gelbe Kuh (1911).

August Macke, who came into frequent contact with Russi and made his own drawings of the dog, prevailed upon Marc to change the name of the painting from the one Marc originally had in mind, So wird mein Hund die Welt sieht.3 We know from Marc that he wanted to show Russi in thought, so the dog’s seated posture suggests that this is what is happening in the stillness. The strange view of the landscape Russi “sees” is nonetheless completely identifiable as a typical one from around Sindelsdorf where Marc lived. By placing buildings in the recognizable, managed farmlands of Bavaria, Marc suggests that people and animals are part of the same ecology, which, for dogs as the primary animal of domestication, is certainly true.

Russi did not have the life of a working dog, instead, with Marc, dividing his time between Munich, Berlin, and the small towns of Sindelsdorf and Ried. Russi lost part of his tail in 1911, an adjustment to his appearance that is reflected in his 1912 portrait. This shows that Marc had a commitment to showing morphologically accurate details even about the animals he painted, even as the paintings themselves broke with academic naturalism.

Die gelbe Kuh,

Franz Marc, 1911

189.2 × 140.52 cm

Oil on canvas

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. That is Russi Marc in the lower left corner.

[1] Franz Marc, Briefe, Schriften und Aufzeichnungen, (Leipzig: Kiepenheuer, 1989), 11. Observing Russi at this moment, Marc wonders: “Ich möchte mal wissen, was jetzt in dem Hund vorgeht.”

[2] Marc, Briefe, 196-197.

[3] Franz Marc, August Macke, Briefwechsel, (Köln: DuMont, 1964), 124-126.