by Jean Marie Carey | 7 Jun 2017 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Dogs!, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

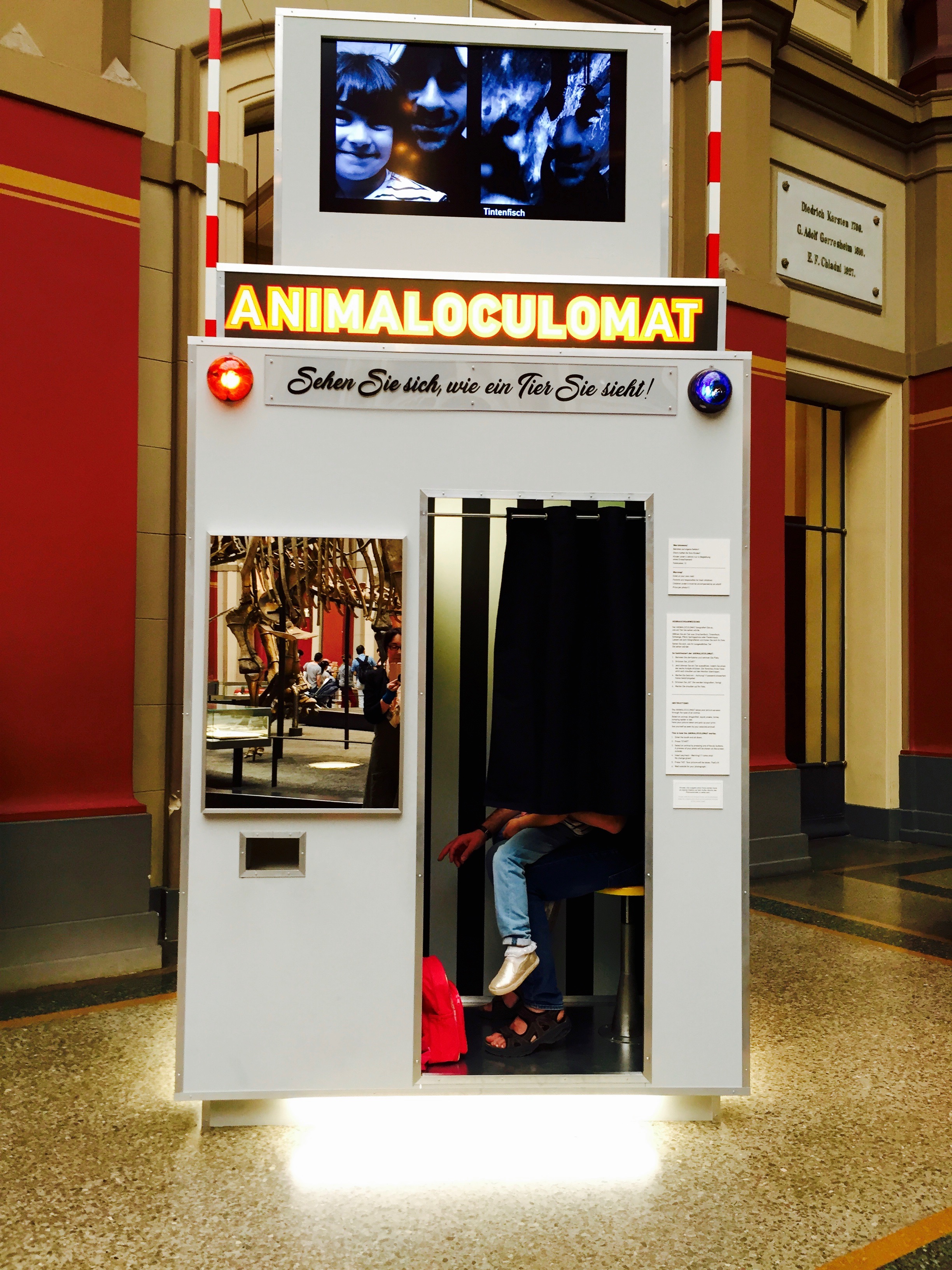

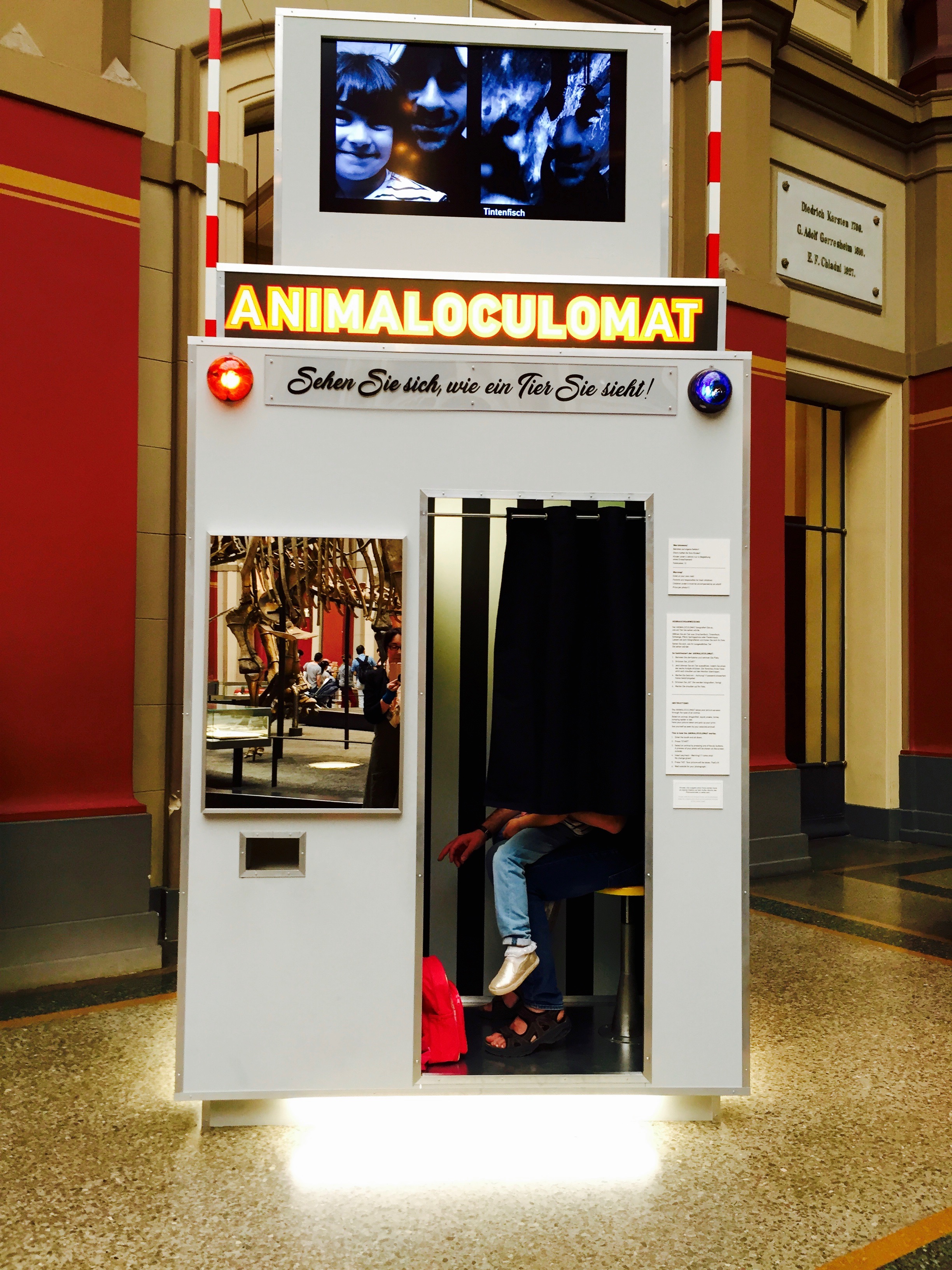

Klara Hobza, Animaloculomat, 2017

Already by 1909 Jakob Johann von Uexküll had, in Umwelt und Innenwelt der Tiere, given a great deal of consideration to the „Innenleben“ of animals. For Franz Marc this led to the question of how a horse, an eagle, a deer, or a dog saw and experienced the world, prompting the reflection „die Tiere in eine Landschaft zu setzen, die unsren Augen zugehört, statt uns in die Seele des Tieres zu versenken, um dessen Bildkreis zu erraten“.[1]

A painting like Liegender Hund im Schnee, a depiction of Marc’s dog Russi, radiates the oneness between the surrounding nature and the resting dog – „eine gemeinsame Stille von belebter und unbelebter Natur.“[2] .“ But Marc was interested in the actual physical reality of the dog’s vision as well.

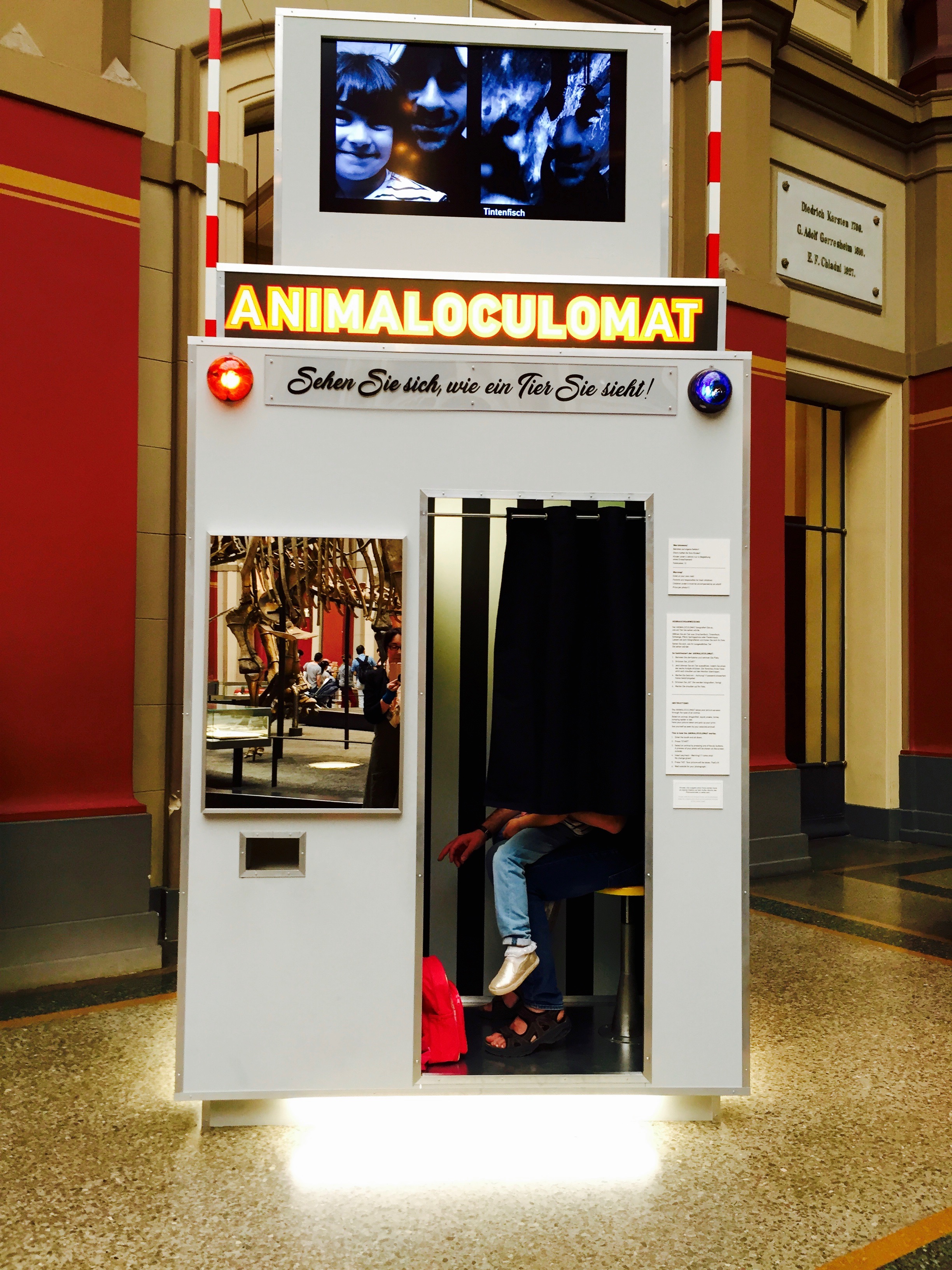

Inside Klara Hobza’s Animaloculomat

by Jean Marie Carey | 27 Oct 2014 | Animals, Animals in Art, German Expressionism / Modernism

The Cry of Nature: Art and the Making of Animal Rights

I got a note from the nice people at Sehepunkte about the review of Stephen Eisenman’s The Cry of Nature I wrote (which is posted on Sehepunkte’s website):

“Sofern Sie über eine eigene Präsentation im Internet verfügen, würden wir uns freuen, wenn Sie dort Ihre Rezension und unser Journal verlinken würden. Hierfür können Sie gerne auch eines unserer Logos … verwenden…”

…so of course, OK! I really like Sehepunkte and am working on some more stuff for them too.

So here the logo: 🙂

Now a few months after reading it, I should report that this book has had a nice slow burn and even though this is a very positive review I think I would rate it even more highly now, particularly as a teaching text as it covers a broad subject area still with clarity and depth in each chapter. I was able to use Eisenman’s section on the hunting practice of indigenous peoples, for example, as a point of reference in a recent seminar I gave for the Bioethics Centre at the university and in reference to a discussion about the dolphin massacre in Taiji, Japan. (To support my argument against hunting and hunters I mean: Don’t get me wrong; there’s no place for humans who hunt in any universe, and people trying to be “open minded” about hunting are without fail patronizing, paternalistic, and dead inside.)

Anyway, this is an excellent book and here is the review:

(Stephen F. Eisenman: The Cry of Nature. Art and the Making of Animal Rights, London: Reaktion Books 2013, ISBN 978-1-78023-195-2).

Art historical texts, and especially single-authored volumes, should be judged in great measure by how well they fulfill their expressed ambitions. By this rule The Cry of Nature. Art and the Making of Animal Rights, whose central objective is to provide an intellectual and informational resource for readers interested in the intersection of the animal studies and the making of art, and a platform for scholars to reflect on provocative subjects suggested by the twining of these two themes, must be deemed a success.

Each of its chapters contributes to author Stephen F. Eisenman’s goal of addressing and evaluating important issues pertaining to the contemporary discussion of animal rights and the movement’s connection to art and ideas originating in the 18th century as well as, to some extent, before. Organized into five chapters and a strong introduction and conclusion, plus a recommended reading list of some of the foundational volumes of the relatively new discipline of animal studies, the book surveys not only images but historicizing texts and makes a strong claim that something like an animal rights movement has existed since antiquity, springing into cohesion in the 1700s, with artists making and using images as persuasion and propaganda.

The pleasure derived from reading this book lies partially in the richness of Eisenman’s detailed, personal, and confident descriptions of the lives and emotions of real animals, making his prose eminently accessible. Readers will be compelled by the forcefulness of local histories about, for example, a majestic African elephant photographed in a moment of perfect stillness at a watering hole in 2007 who is killed by poachers in 2009, and delighted by anecdotes about Echo, the author’s dog, who learns to stage pratfalls and tumbles in order to make Eisenman laugh. These stories are integrated meticulously within more formal discussions of images – some well-studied, including Rosa Bonheur’s The Horse Fair (1853) and Jean-Baptiste Oudry’s A Hare and a Leg of Lamb (1742), some less famous – such as Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri’s 1975 painting Eagle Dreaming – which are produced about, and in mindfulness of, the animal.

The book begins with a background chapter defining “What is an Animal?” in terms of societal mores and biological evidence about the commonalities and differences amid living creatures, centering on the ability of animals to communicate, to experience emotions, and to feel pain. This chapter includes pleasantly unexpected exemplars, such as Simon Tookoome’s 1979 linocut I Am Always Thinking of Animals, as it stakes out the moral and practical discussions around how we define language and consciousness.

The chapters “Animals into Meat” and “Counter Revolution” dwell on images of the corpses of animals, shown as food, prey, and sacrificial stand-in for the human figure and body. While the recurring motif of the flayed ox in paintings by Gustave Caillebotte and Rembrandt may arouse as much distancing disgust as identification, Eisenman’s delicate examination of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s The Ray (1728) makes persuasive on the page that these artists intended to convey their beliefs in the existence of the souls and consciousness of animals, and commensurately, the dismal mortality of humans, on their canvases. (more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 23 Jun 2010 | Art History

The First Thilling Chapter

WARNING!

The Inspector for the Office of Literary Quality, a unit of the British Colonial Office, has determined that the following reading material is of the poorest possible grade, as it is solely structured around nonsense and simply “meaningless words on a page.”

This material is not intended for resale, and is the property of the University of Polyleritae.

Any infringement of the Statuatory Copywright by Dr. Moe Howard and the University is a violation of all applicable laws.

Please note that the names have been changed in order to encourage innocent parties to commit acts that would adulterate their innocence.

This is the first installment of the Tom Selleck/Opus the Penguin Literary Collection.

The University would like to thank you for helping us to establish the finest in InstiLit. Please remember that THIS IS A SECURED BUILDING. NO RIFF-RAFF. NO WHISTLING IN THE HALLS OR PLAYING WITH THE ELEVATORS.

THANX,

The University of Polyleritae

by Jean Marie Carey | 1 Jun 2010 | Art History

Unidentified Coastal Organism

It’s June 2010.

“The end of history involves, then, an ‘epilogue’ in which human negativity is preserved as a ‘remnant’ in the form of eroticism, laughter, joy in the face of death. In the uncertain light of this epilogue, the wise man, sovereign and self-conscious, sees not animal heads passing again before his eyes but rather the acephalous figures of the hommes farouchement religieux, ‘lovers,’ or ‘sorcerer’s apprentices.’ ”

— Giorgio Agamben, The Open: Man and Animal, (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004), 7.

by Jean Marie Carey | 13 Jun 2008 | Art History, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

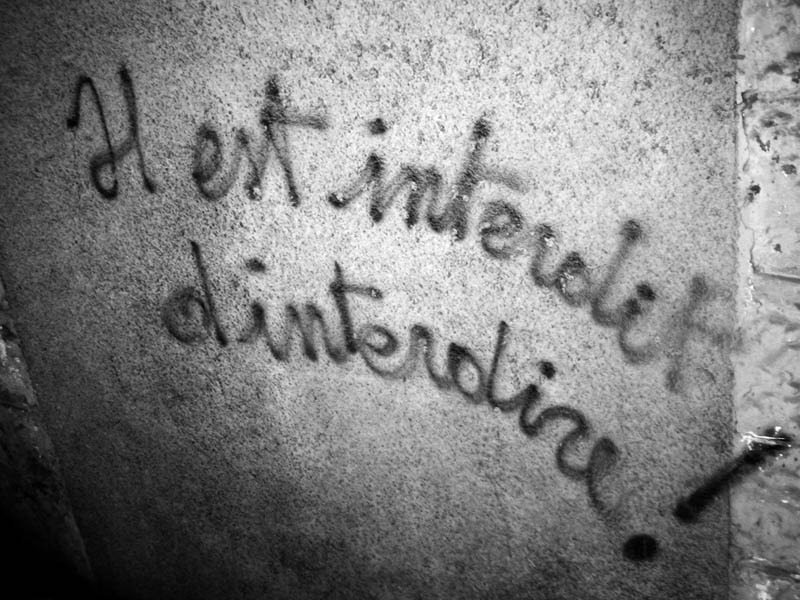

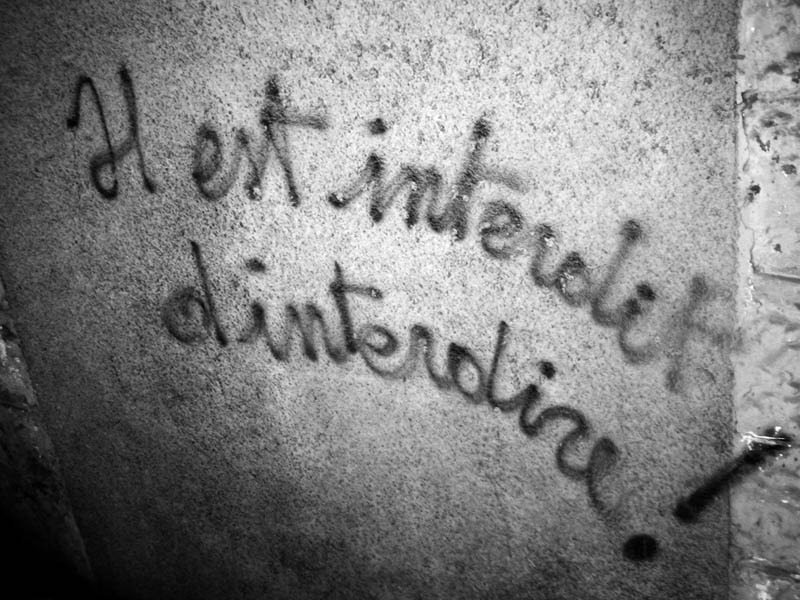

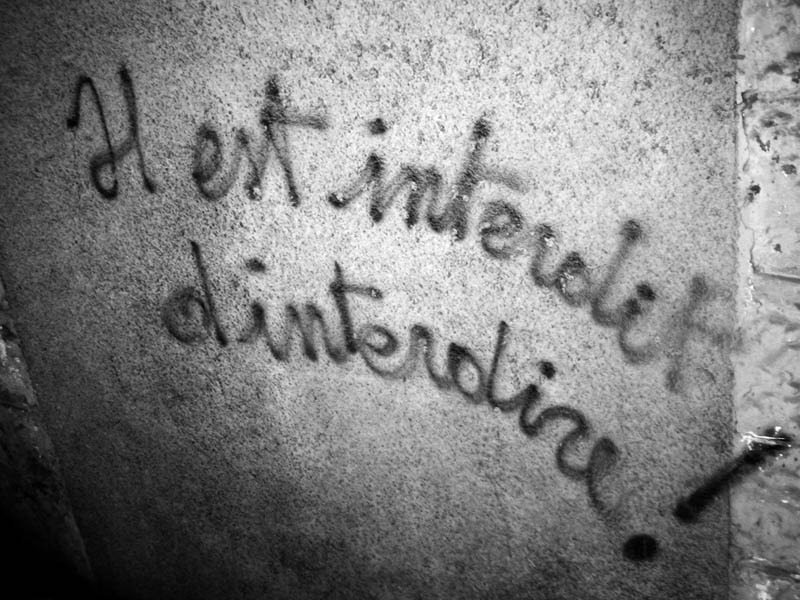

Situationist grafitti, Menton, Occitania, 2006 (the 1968 slogan “It is forbidden to forbid”, with missing apostrophe). Wikipedia Commons

Situationist grafitti, Menton, Occitania, 2006 (the 1968 slogan “It is forbidden to forbid”, with missing apostrophe). Wikipedia Commons

“Rather — just as certain biologists argue for the maintenance of species diversity among plants in order to preseve them for potential use by future generations — we should battle on the side of the obscure, the small, the powerless, the marginalized in order to maintain bio-diversity of memes, of ideas and aesthetic and imaginary realms.”

Marina LaPalma’s “Situationism: A Primer” is one of the best readings in existence for art history students because it is very easy to digest, in terms of distilling the much more difficult prose of situationists from the 1960s, particularly Guy Debord, but also because it is a call to action that clearly illuminates some of the social conditions to be acted against.

Written in 1988 in honor of the approximate twentieth anniversary of the publication of The Society of the Spectacle, “Primer” notes that the intervening decades have made DeBord’s observations seem even more absolutely correct. (Time has done the same for “Primer.”) LaPalma describes a completely dystopic society, yet in the last quarter of the article makes clear that her intent overall mood is hopeful.

Like the original SI group, LaPalma makes a few incorrect assessments, identifying simple sociopathy (“Can any pleasure we are allowed to taste compare with the indescribable joy of casting aside every form of restraint and breaking every conceivable law?”) and the Los Angeles riots as appropriations of situationism.

Yet many – most – of LaPalma’s statements about the Spectacle, like DeBord’s, seem even more valid today than when written: “The world we see is not the real world, it is the world we have been conditioned to see; a world constructed from the black and white of tabloids, a world framed by the mahogany veneer of the television set, a world of carefully constructed illusions – about ourselves, about each other, about power, authority, justice and daily life. A view of life from the perspective of power.”

LaPalma uses the commodification of superficially “rebellious” music (punk and techno) to illustrate the idea of recuperation, and is also, mercifully, extremely critical of hippie-collectivist modes of dropping out. “Revolution is a process, a process that can be started now,” says LaPalma.

The problems – isolation through the work/home/consumer system, totally immersive media that purports to broadcast reality, the replacement of the citizen by the consumer – are clear. The extremity of the endless war, continuous states of celebrity meltdown, and now, recession, makes action seem like the only choice. LaPalma does not provide any guidance for resisting the Spectacle within society without perpetuating it.