by Jean Marie Carey | 12 Mar 2017 | Art History, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism

While I was in New York City for the College Art Association meeting – more on this next post – I was really busy and also sick the entire time. Fortunately though I did get to go to a few museums, and a significant highlight was the Max Beckmann in New York exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Fifth Avenue. (My review of the catalogue of the show for Museum Bookstore is on their blog, and in part below).

When I last left Beckmann in my research, he had forlornly been rejected by the groundbreaking Köln Sonderbund show of 1912 because his work was deemed too old-fashioned. This was found to be hilarious by Beckmann’s self-appointed foil, Franz Marc, who had withdrawn his own work from the Sonderbund on the grounds that the entire exhibit was too old-fashioned and boring for his animal paintings.

Over the years I’ve come to appreciate Beckmann’s devotion to his own vision and embrace of the sort of contemporary history painting that forms an important aspect of the Neue Sachlichkeit, though beyond its opposition to Expressionism, Beckmann did not think himself a part of that or any school or movement.

Staged at the Met in what turned out to be the last week of employment of director Thomas Campbell, my aesthetic reaction was that the paintings, mostly large portraits and a few of his famous triptychs, would have better served Beckmann by being installed in a single large hall. This is a small complaint though because even on a crowded Saturday it was possible to see the paintings well enough.

People were very interested in “Woman with Mandolin in Yellow and Red,” 1950.

(more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 12 Feb 2016 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

Franz Marc, Zwei Katzen, blau und gelb, 1912

The College Art Association conference was held 3-6 February in Washington, D.C., which for what I study is not a very interesting art city in the way New York City is…and D.C. is thus also very expensive to visit, since the trip doesn’t include a few precious hours in the Met, MoMA, Guggenheim, Neue Galerie, and so on.

If conferencing, not museum-visiting, is to be CAA’s focus going forward, the organization should do what the German Studies Association does, and move the meeting to some less-costly destinations that still have good mass transit and more of a range of hotel rooms, like Las Vegas or Atlanta.

This conference I had a lot of tasks I actually had to do, and one I wanted to do, or I should say was very curious about doing, attending the Historians of German, Scandinavian and Central European Art, or HGSCEA, [formerly just HGCEA, but, I guess the Munch people or something…] meeting, which this year took the form of a dinner honoring the long-reigning and undisputed chief Kandinsky scholar, Rose Carol Washton Long of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and Charles Haxthausen from Williams College.

I took the cryptic “honoring” on the invitation to mean “retiring,” which put me in mind of The King of the Cats. Miss Jessel’s “Haunted Palace” blog gives a nice account of the oral history tradition of this tale and its place in the folklore of the British Isles but, basically, without belaboring the point the outstanding extra-narrative moral for cat lovers and observers is probably that upon learning of the death of “the king of the cats,” all cats think that they are the designated heir to the throne.

So with respect to the fractious group of people who comprise known Kandinsky scholars…without an obvious heir apparent (to my mind there is not one, the once-promising regent having chosen their battles poorly), wouldn’t they all be prepared for anointment? As it turned out RCWL, in her very congenial speech, immediately made clear that while she was retiring from CUNY, she would not be relinquishing the reins to the Kandinsky dynasty anytime soon.

The “party” itself was quite a mysterious affair in that it did not appear as an “affiliated society” event anywhere on the CAA schedule (or the new Linked-In developer-sponsored) app, and was held in a small restaurant in Adams Morgan which was entirely closed except for the HSGCEA dinner. RSVP, affiliation, and credentials were thoroughly vetted at the door, and there were no nametags. Nametags would not have been much use anyway, since everyone went by a non-apparent nickname, like “Ricki” or “Mark.” And it was very dark inside the restaurant, Lillie’s (actual lighting shown), and you couldn’t see even across the room. So in other words it was pretty much how I expected it to be, except there wasn’t any kind of St. Bartholomew’s day type of fracas, duel, or mass feline exit through the fireplace.

The “party” itself was quite a mysterious affair in that it did not appear as an “affiliated society” event anywhere on the CAA schedule (or the new Linked-In developer-sponsored) app, and was held in a small restaurant in Adams Morgan which was entirely closed except for the HSGCEA dinner. RSVP, affiliation, and credentials were thoroughly vetted at the door, and there were no nametags. Nametags would not have been much use anyway, since everyone went by a non-apparent nickname, like “Ricki” or “Mark.” And it was very dark inside the restaurant, Lillie’s (actual lighting shown), and you couldn’t see even across the room. So in other words it was pretty much how I expected it to be, except there wasn’t any kind of St. Bartholomew’s day type of fracas, duel, or mass feline exit through the fireplace.

As to my own paper and panel, I was thrown off my presentating game a little – not a lot, or not as much as I had expected or was undoubtedly intended – and got a lot of good questions, including some very specific queries from some more-than-casual idolators about Animalisierung, of all things, about the painting Tierschicksale, and about what I had specifically set out to talk about, affect/effect disturbing/calming animal images have upon human animal/human-animal empathy.

Basically my claim is that disapprobation toward animal abusers – such as generated by the film The Cove and the work of Sue Coe – is not as strong a motivator as true identification with the animal subject. Hence the focus on Franz Marc. This isn’t necessarily as obvious an idea as it seems, and bears more discussion and exploration (which is why I am writing about it).

by Jean Marie Carey | 29 Aug 2015 | Animals, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism

My 2012 M.A. thesis, Franz Marc as an Ethologist, is now part of the online collection of the open-access Social Science Research Network (SSRN). You can download it or look at the abstract here.

UPDATE: I just can’t with Elsevier’s involvement with SSRN. In addition to Elsevier being generally evil, not supporting open access, and ruining the Pergamon imprint, more than a year after acquiring SSRN, there is still no discrete art history rubric, or way for authors to track who is looking at their work. But mainly Elsevier is garbage.

Franz Marc, Rehe im Schnee II, 1911, one of Marc’s paintings discussed in my thesis.

by Jean Marie Carey | 7 Jun 2015 | Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc

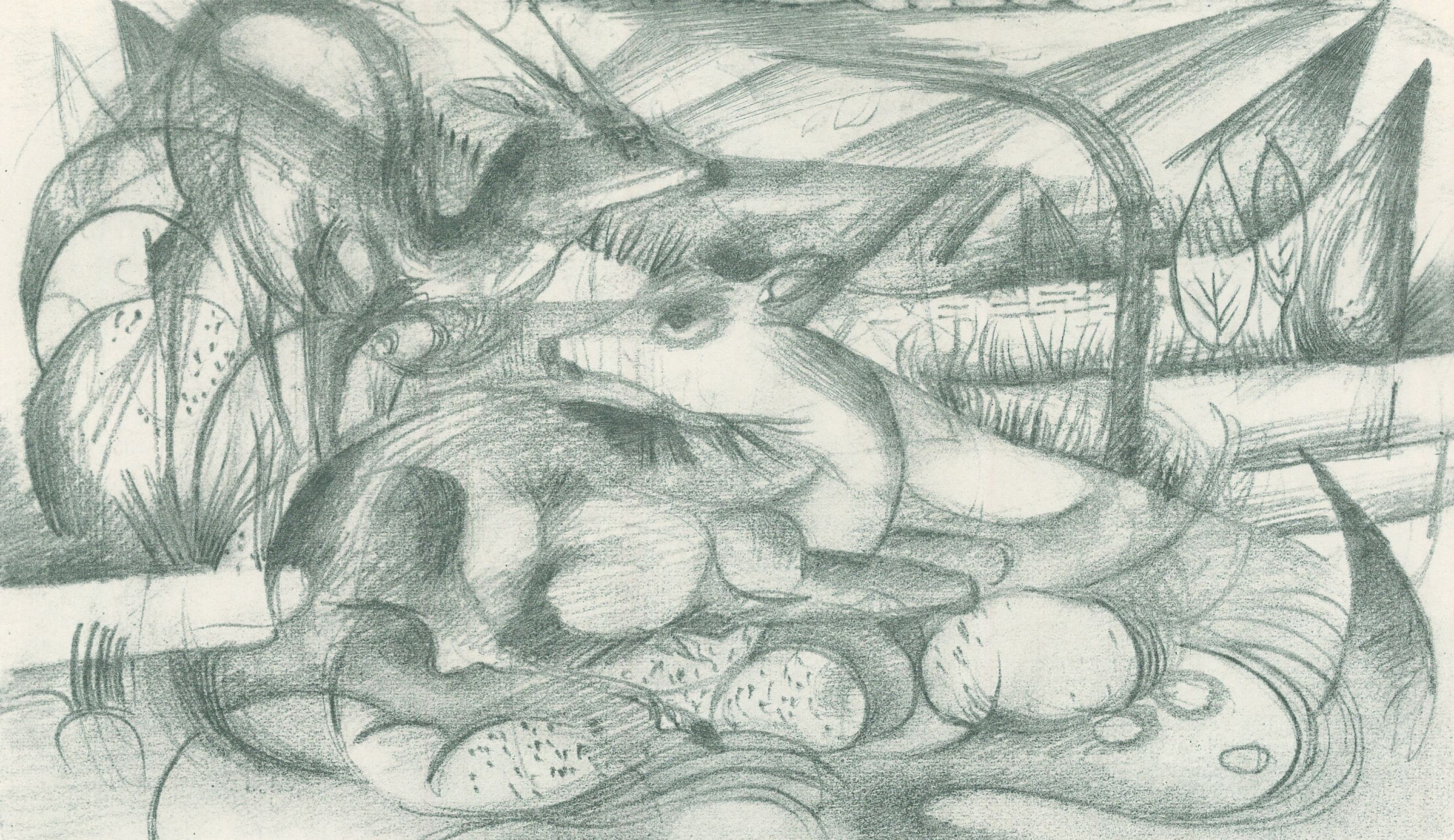

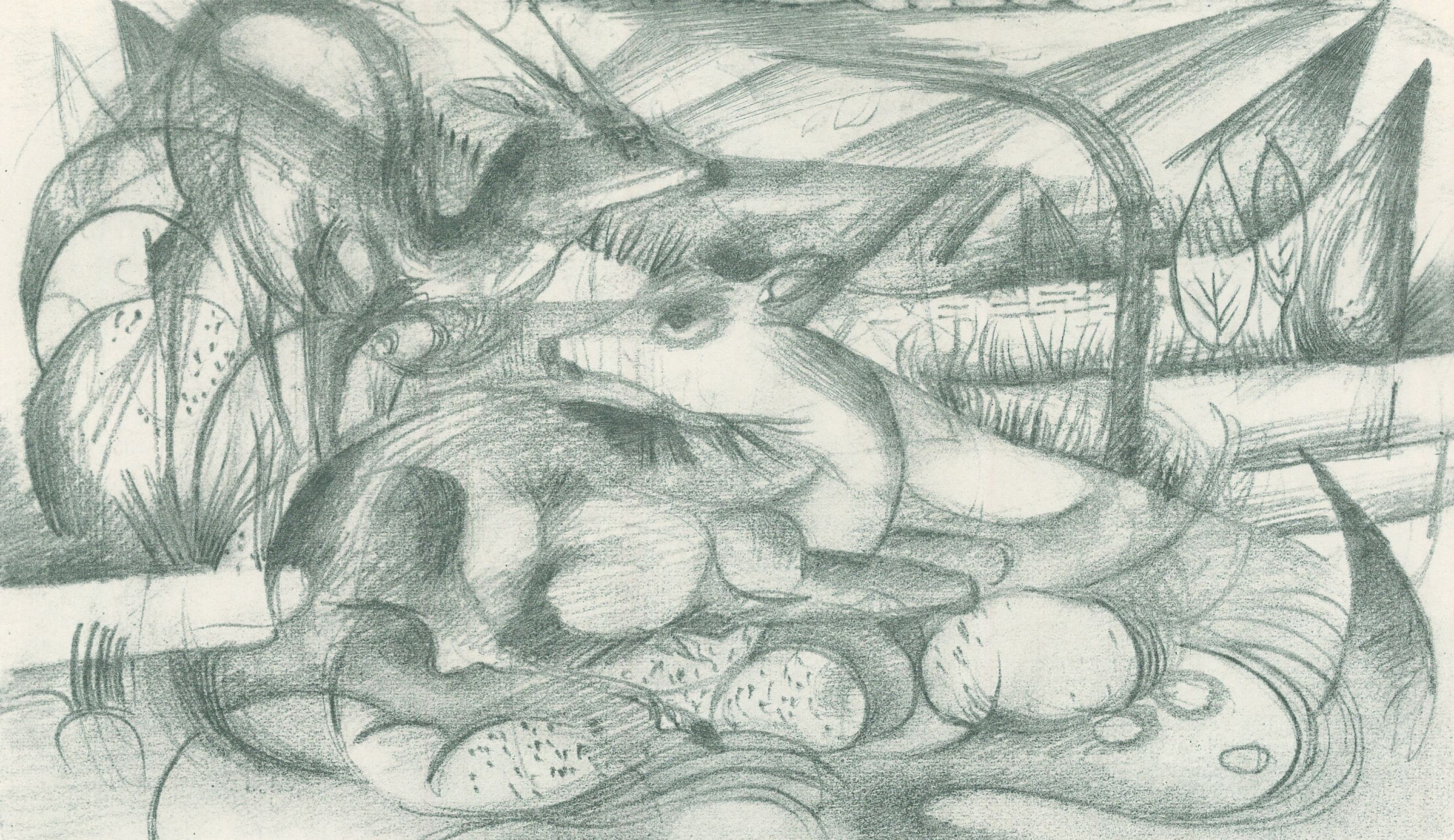

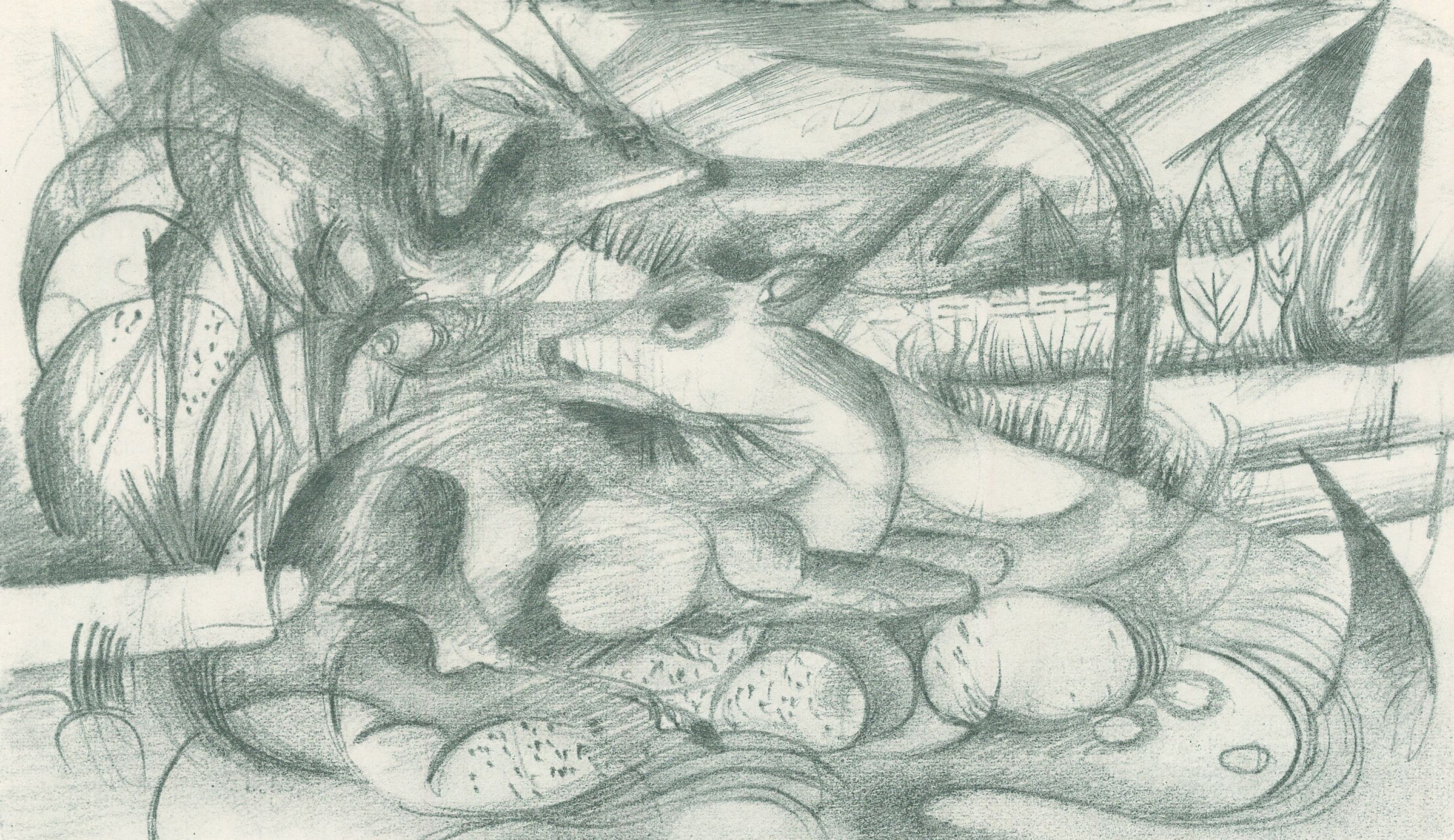

Franz Marc, Skizzenbuch aus dem Felde, Skizze 24, 1915

I recently looked harder at Franz Marc’s experiments with poetry. I think you could say that much of Marc’s writing borrows structurally from poetry, and Marc read a lot of poetry, including all of the classics you’d expect, work by people he actually knew, such as Gottfried Benn and Else Lasker-Schüler. He was also interested in French Symbolist Stéphane Mallarmé, particularly Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard of 1897, having extensively annotated a copy of the text; contact with Hugo Ball, who was influenced by Mallarmé’s text/design, probably heightened Marc’s attention.

From 1912 Marc made doodles of lines of the following poem here and there, and of course the last line is what Marc had originally intended to be the title of the painting we know as Tierschicksale (1914). But it was not until 1915 he wrote these phrases down all together in his small portfolio of drawings made in Germany and France, during the war. It’s hard to say what the poem means, especially in the context of the (approximately – some leaves may be lost) 35-page sketchbook’s compact animal images, it is very interesting. A translation is elsewhere but here is the original poem:

“…ein rosafarbner Regen viel [sic] / auf grüne Wiesen. / die Luft war wie grünes Glas. / das Mädchen [sah auf’s] blickte ins Wasser; das Wasser war klar [rein] wie Kristall; da weinte das Mädchen. / die Bäume zeigten ihre Ringe; die Tiere ihre Adern”.

(Abgedruckt in: Klaus Lankheit: Franz Marc: sein Leben und seine Kunst. Köln: DuMont 1976, S. 124.)

by Jean Marie Carey | 6 Apr 2015 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, August Macke, Dogs!, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL

Hund vor der Welt, Franz Marc (1912). Oil on canvas, 118 by 83 centimetres, private collection, Switzerland

I write about this painting a lot – in fact I once, for quite a long time, devoted my academic research solely to this painting – but I realised I don’t often say anything about it in this space. So here is a little excerpt not from my current chapters but from a side project.

§ § §

Franz Marc made an innovative painting – a metaphysical genre portrait of his dog Russi – called Hund vor der Welt in the spring of 1912. The large vertical canvas shows the white hound seated on a hillside, facing the sun and the landscape at an angle across an indeterminate space. We have an account of what Marc had in mind in making this image in particular and Marc’s other thoughts about painting his frequent model.[1] There is also a substantial amount of documentation about Russi, the dog, who, as the artist’s constant companion, was a character who populated the art, photographs, and writing of other people. We even know where Russi was born, how he came as a puppy to live with Marc, and when he died.[2] So despite its slightly whimsical affect, Hund vor der Welt is an image of a real dog about whom much historical information is available. Marc made many paintings in which Russi also appears as a peripheral regular “character;” he leads the way in Im Regen (1912) and leaps after Die gelbe Kuh (1911).

August Macke, who came into frequent contact with Russi and made his own drawings of the dog, prevailed upon Marc to change the name of the painting from the one Marc originally had in mind, So wird mein Hund die Welt sieht.3 We know from Marc that he wanted to show Russi in thought, so the dog’s seated posture suggests that this is what is happening in the stillness. The strange view of the landscape Russi “sees” is nonetheless completely identifiable as a typical one from around Sindelsdorf where Marc lived. By placing buildings in the recognizable, managed farmlands of Bavaria, Marc suggests that people and animals are part of the same ecology, which, for dogs as the primary animal of domestication, is certainly true.

Russi did not have the life of a working dog, instead, with Marc, dividing his time between Munich, Berlin, and the small towns of Sindelsdorf and Ried. Russi lost part of his tail in 1911, an adjustment to his appearance that is reflected in his 1912 portrait. This shows that Marc had a commitment to showing morphologically accurate details even about the animals he painted, even as the paintings themselves broke with academic naturalism.

Die gelbe Kuh,

Franz Marc, 1911

189.2 × 140.52 cm

Oil on canvas

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. That is Russi Marc in the lower left corner.

[1] Franz Marc, Briefe, Schriften und Aufzeichnungen, (Leipzig: Kiepenheuer, 1989), 11. Observing Russi at this moment, Marc wonders: “Ich möchte mal wissen, was jetzt in dem Hund vorgeht.”

[2] Marc, Briefe, 196-197.

[3] Franz Marc, August Macke, Briefwechsel, (Köln: DuMont, 1964), 124-126.