Every so often, a fragrance saunters into the market, demanding our attention with an air of undeserved audacity. Jean Paul Gaultier's Divine (2023), however, feels less like a sophisticated, daring entry and more like a grandiloquent crash. Its limited notes of...

bauhaus imaginista

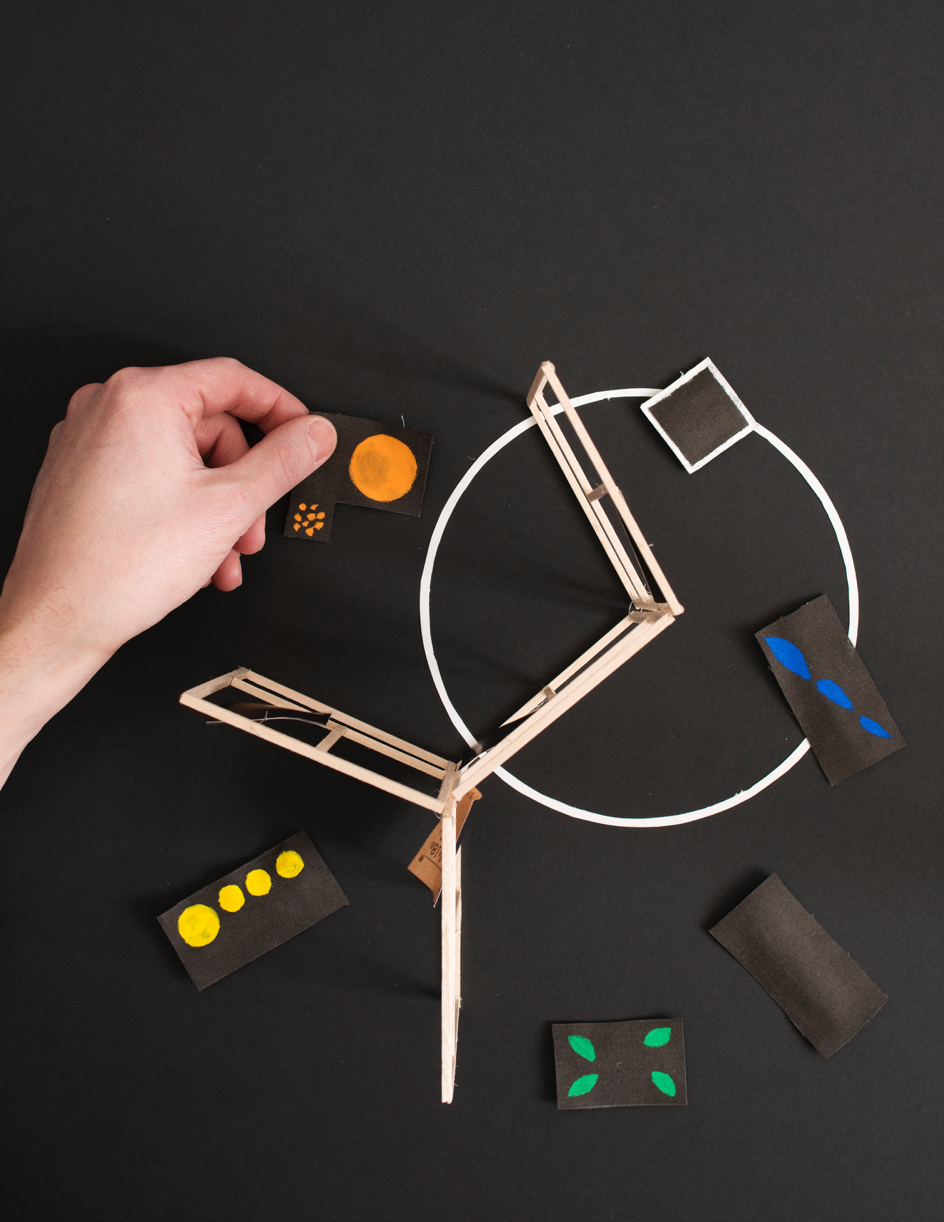

Luca Frei, Model for a Pedagogical Vehicle, 2017. Photo: Karl Isakson.

bauhaus imaginista is, or was since it’s taken a while to get this post together, an international exhibition project examining the global influence of the Bauhaus on the centennial of the founding of the school in Weimar, Germany. bauhaus imaginista’s main event, Bauhaus Week Berlin, ran 30 August through 8 September 2019, but other showcases and one-off events go through the end of the year. Headquartered at the Festival Center at Ernst-Reuter-Platz (Mittelinsel) in Berlin-Charlottenburg, the art festival includes tours of the Mies van der Rohe Haus, demonstrations of Josef Albers’ glassworks techniques, exhibits of Bauhaus printing and typography, weaving and ceramics workshops, tours of Bauhaus architecture, and re-created shop windows. Here I am condensing a review of the very comprehensive catalogue of the global exhibition, which ran in full at Museum Books, and of the exhibition, featured in ArteFuse. For a complete schedule of events, see https://www.bauhaus100.berlin/

Coming soon some very interesting provenance news – a triple header!

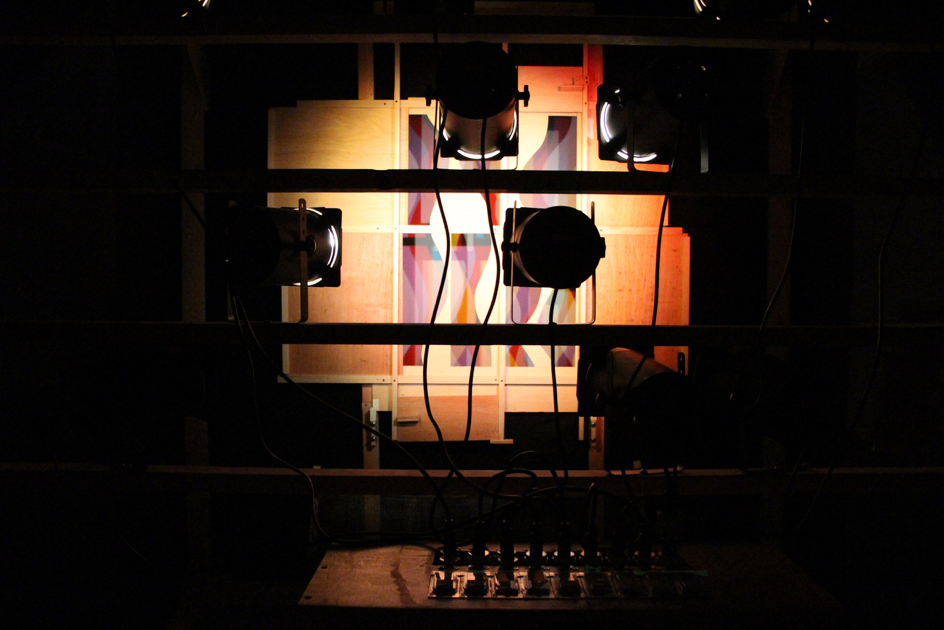

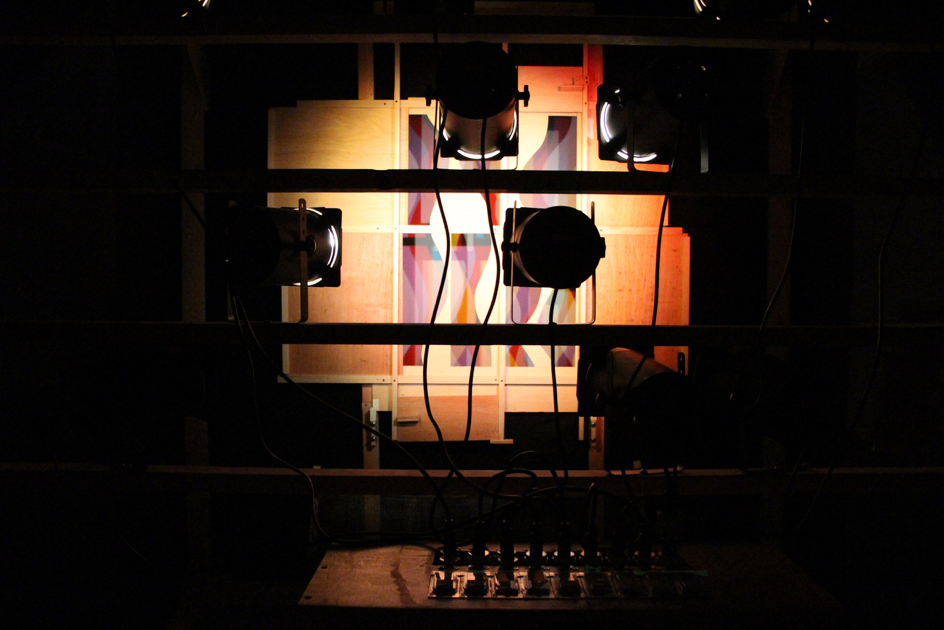

Kurt Schwerdtfeger, Reflektorische Farblichtspiele, 1922. Courtesy of Microscope Gallery and Kurt Schwerdtfeger Estate © 2016.

Satellites of bahaus imaginistaare ongoing around Germany. In Leipzig an exhibition showcasing the academy’s material culture focus is open through 29 September 2019 at the GRASSI Museum für Angewandte Kunst, with well-known manufactured items made in Saxony’s factories face contemporary examples of applied design and craft. The exhibition History, Present and Future of a City presented by the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart through 20 October 2019 and is a collection of reflections by contemporary artists on the interaction of the Bauhaus with international influences.

The series of Bauhaus centennial symposiums, classes, performances, and exhibits began in March 2018 with an academic conference at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou and will conclude at Nottingham Contemporary in England with the show Still Undead: Pop Culture in Britain Beyond the Bauhaus, opening 21 September 2019 and running until 5 January 2020; bauhaus-imaginista.org is the online journal of the project.

Nandalal Bose, Anleitung zur Wandmalerei, 1929/30. Fresco on cement wall, 80 x 100 cm.Kala Bhavana, India.

On the centennial of the founding of the Bauhaus school in Weimar, an ambitious exhibition project, touring 11 countries, is revisiting – and in some cases challenging and sideswiping – the pervasive influence of the academy. Curated and directed by Marion von Osten of Berlin and London-based Grant Watson, the individual parcels of the bauhaus imaginistaare complemented by a program of cross-hemispheric satellite events, workshops, and panels. The confluence with the current critique-of-Modernism zeitgeistis fortuitous for the project, because otherwise I am not sure that bauhaus imaginistaposes a provocative question that requires a jusqu’au bout du monde-style breakneck global investigation to answer: The existence of the Nike Air Max 270 React ‘Bauhaus’ trainer seems substantive proof that the Bauhaus is both certifiably reify-able and has a broad popular influence. Notably, with most German-side events taking place in Berlin, Weimar’s present-day incarnation as an out-of-the way village with only one coffee shop to greet disappointed architecture students making the pilgrimage is glossed over.

Paulo Tavares, DES-HABITAT, 2018.

However, 15 years after the dueling canonical polemics of Okwui Enwezor’s “Mega-Exhibitions and the Antinomies of a Transnational Global Form” and George Baker’s “The Globalization of the False: A Response to Okwui Enwezor” appeared in The Biennial Reader(Berlin: Hatje-Cantz, 2004) the sprawling exhibition does provide evidence of an interesting art world mutation. While Enwezor was cautiously optimistic that the global art fair phenomenon would open a cultural sphere for the inclusion of artistic practices beyond the West, Baker argued that such festivals were no more than a consolidation of hegemonic bourgeois culture, and thus by definition Eurocentric and nationalistic.

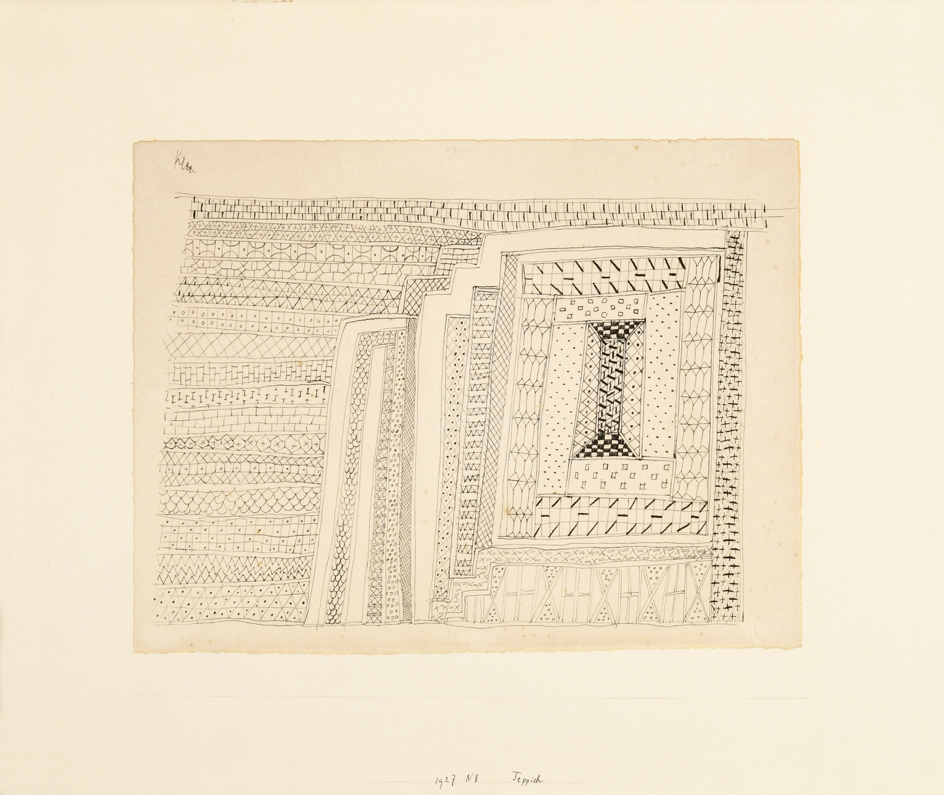

Paul Klee, Teppich, 1927. Pencil on paper and cardboard, 23 x 30 cm. Hans Snoeck Collection, New York.Photo: Edward Watkins

What has happened in the intervening years has been both predictable, as in the rise of the value and popularity of contemporary Chinese art, and surprising. Despite its widespread panning and numerous financial peccadilloes, Kassel’s 2017 Documenta 14 didhave some startling entries, from the breakout durational performance of the women of iQhiya, a collective of University of Cape Town alumnae, to the seemingly incontrovertible solution of the 2006 murder of Halit Yozgat in the installation by The Society of Friends of Halit. The cheekily named Oslo “Biennial” began this summer and runs through 2024…to be followed by the next Oslo Biennial in 2025.

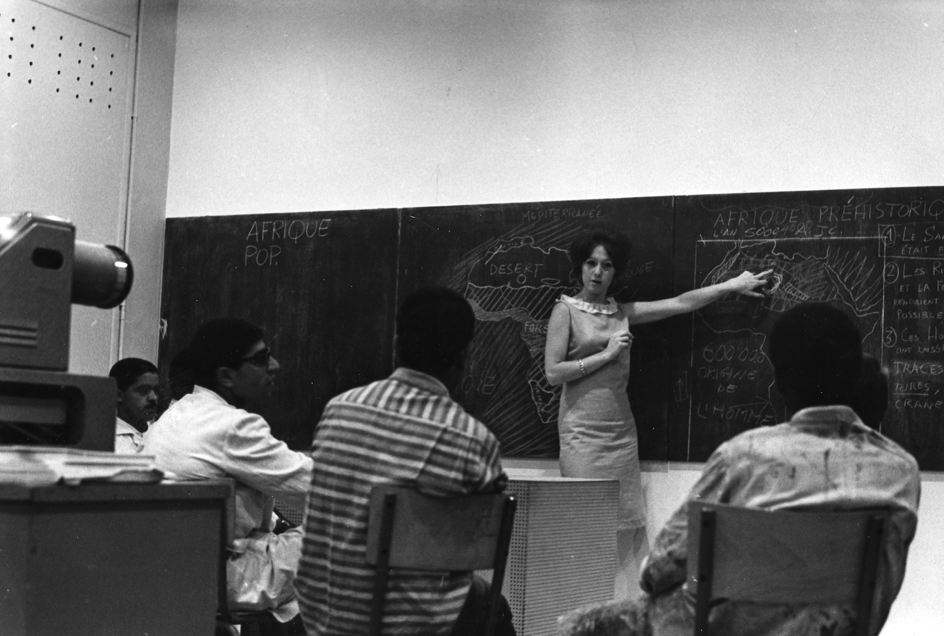

Toni Maraini teaches an art history class at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Casablanca, 1965.Photo by Mohammed Melehi,courtesy of Toni Maraini.

Hannes Meyer, Skizze in einem Dummy für ein Bauhausbuch, c. 1950.GTA Archiv / ETH Zürich, © Hannes Meyer.

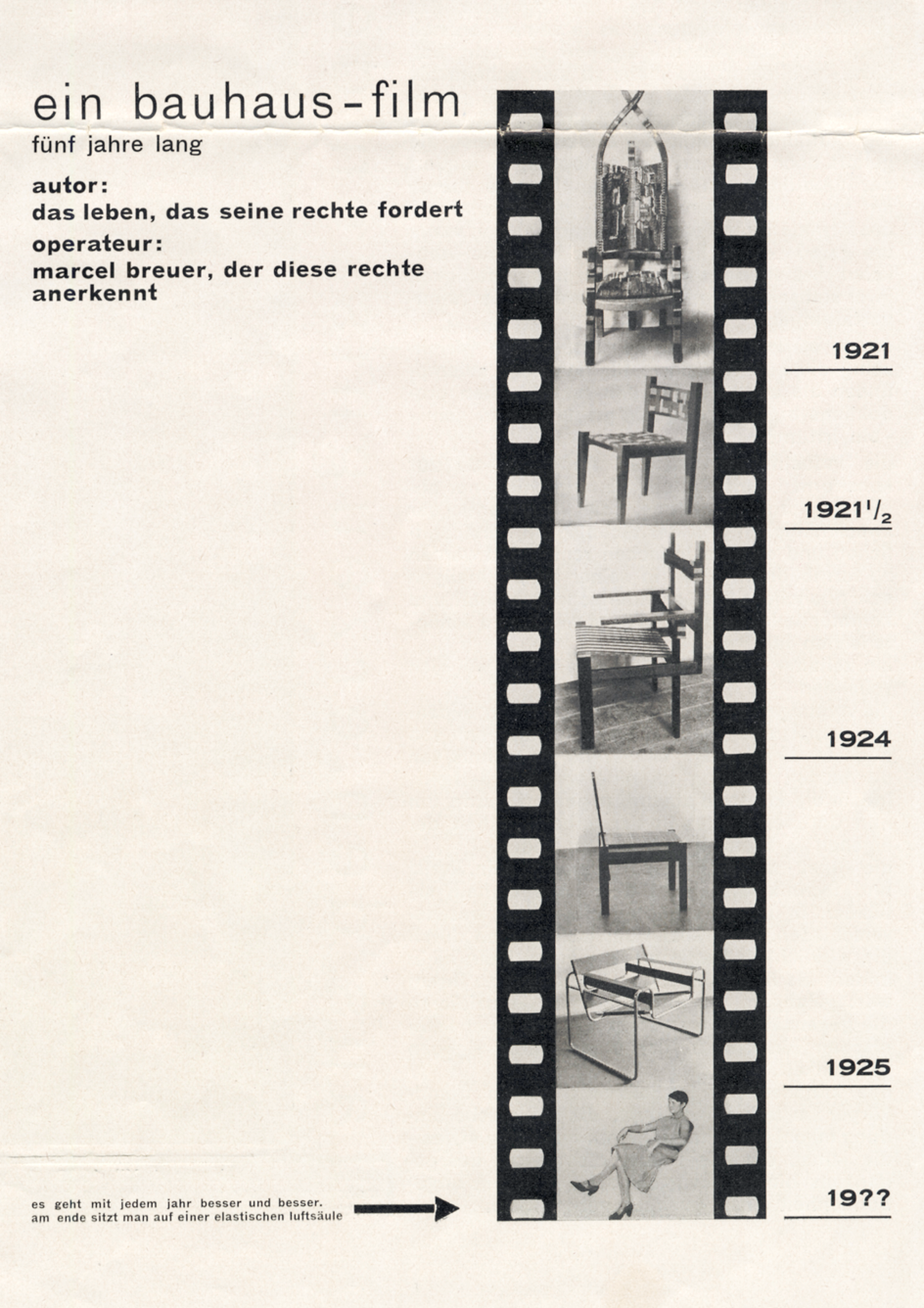

bauhaus imaginista’s distinction is that it is likely that not one single person has seen every instantiation of the concept show. Thus a catalogue for the project edited by von Osten and Watson is valuable as an artefact for the curious and as an interesting volume in its own right (London: Thames & Hudson, 2019). The four thematic movements of the project correspond with the four sections of the catalogue, each based upon one specific Bauhaus object: The Bauhaus Manifesto of 1919; a collage by Marcel Breuer; a drawing of a patterned carpet by Paul Klee; and a light game by Kurt Schwerdtfeger. Theoretically these form the framework for bauhaus imaginista, within which specific themes, historical genealogies, and contemporary debates were to be developed. Fortunately, the catalogue content itself is rich in images of concurrent and archival works, and the individual essays are relatively short and didactic.

Doreen Mende, Hamhung’s two Orphans, 2018. Photo: Silke Briel; © Doreen Mende, Silke Briel.

Marcel Breuer, ein bauhaus-film. fünf jahre lang, 1926. From: Bauhaus, vol. 1, 1926, Offset print, 42 x 29.7 cm. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin.

The Bauhaus was in contact with institutions in many countries, where it encountered similar movements that had arisen independently of it, and that lent the Bauhaus itself strong stimuli. The bauhaus imaginistacuratorial mission of commenting on this simultaneity was expressed in newly commissioned works by Kader Attia, Luca Frei, Wendelien van Oldenborgh, the Otolith Group, Alice Creischer, Doreen Mende, Adrian Rifkin, and Zvi Efrat.During the remainder of the exhibition, taking place in Germany with one more satellite show Nottingham, local art and design movements will be paired with artefacts of the historical avant-garde to memorialize the Bauhaus as well as with processes of decolonization

Takehiko Mizutani, Studie zum Simultankontrast (Unterricht Josef Albers), 1927.Gouache on cardboard; 80.4 x 55 cm. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin.

Ceramics by Marguerite Wildenhain at Luther College, Decorah, Iowa, USA, 2016.Photo: Grant Watso