by Jean Marie Carey | 20 Jan 2017 | Art History, August Macke, Expressionismus, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, Helmuth Macke

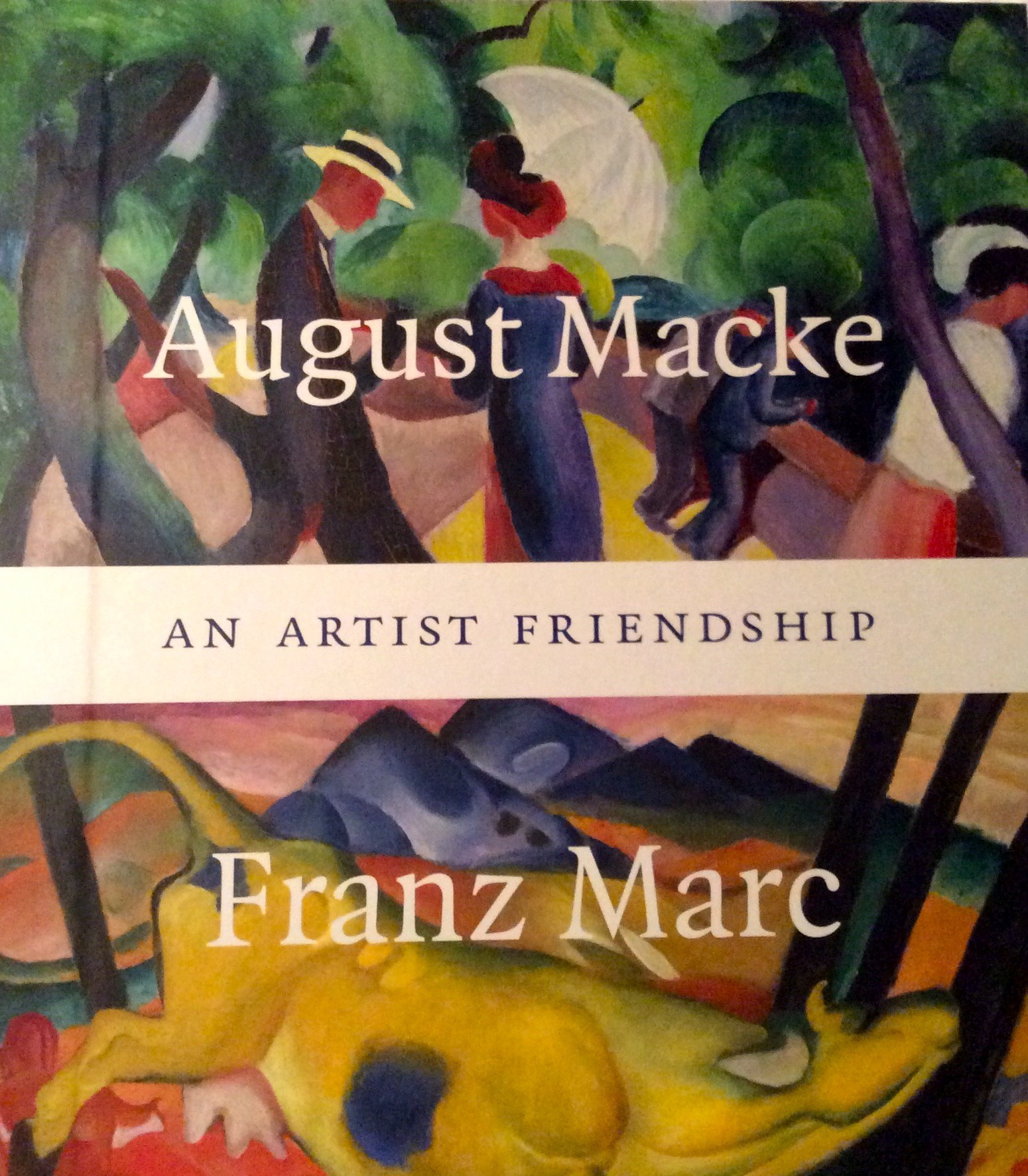

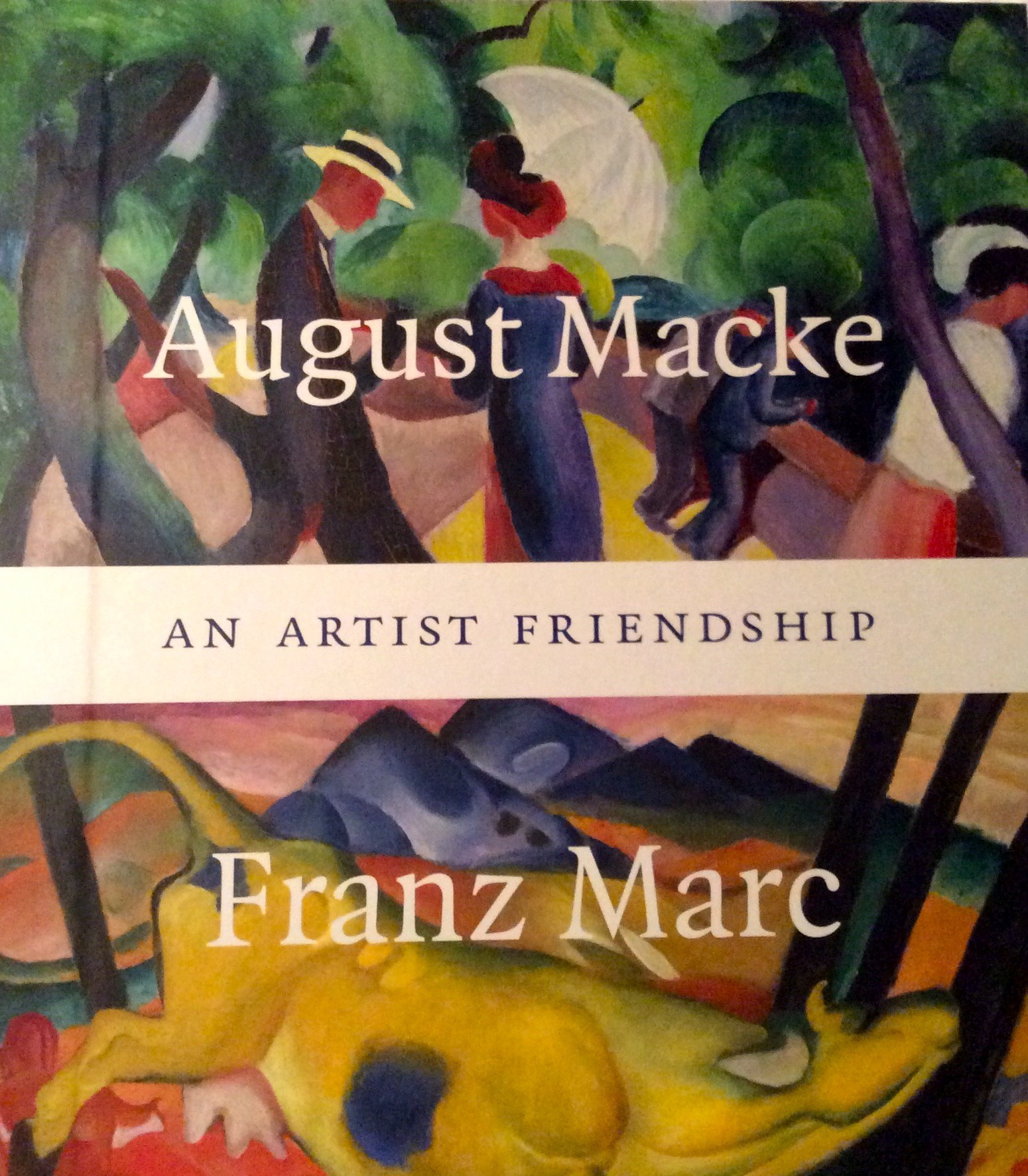

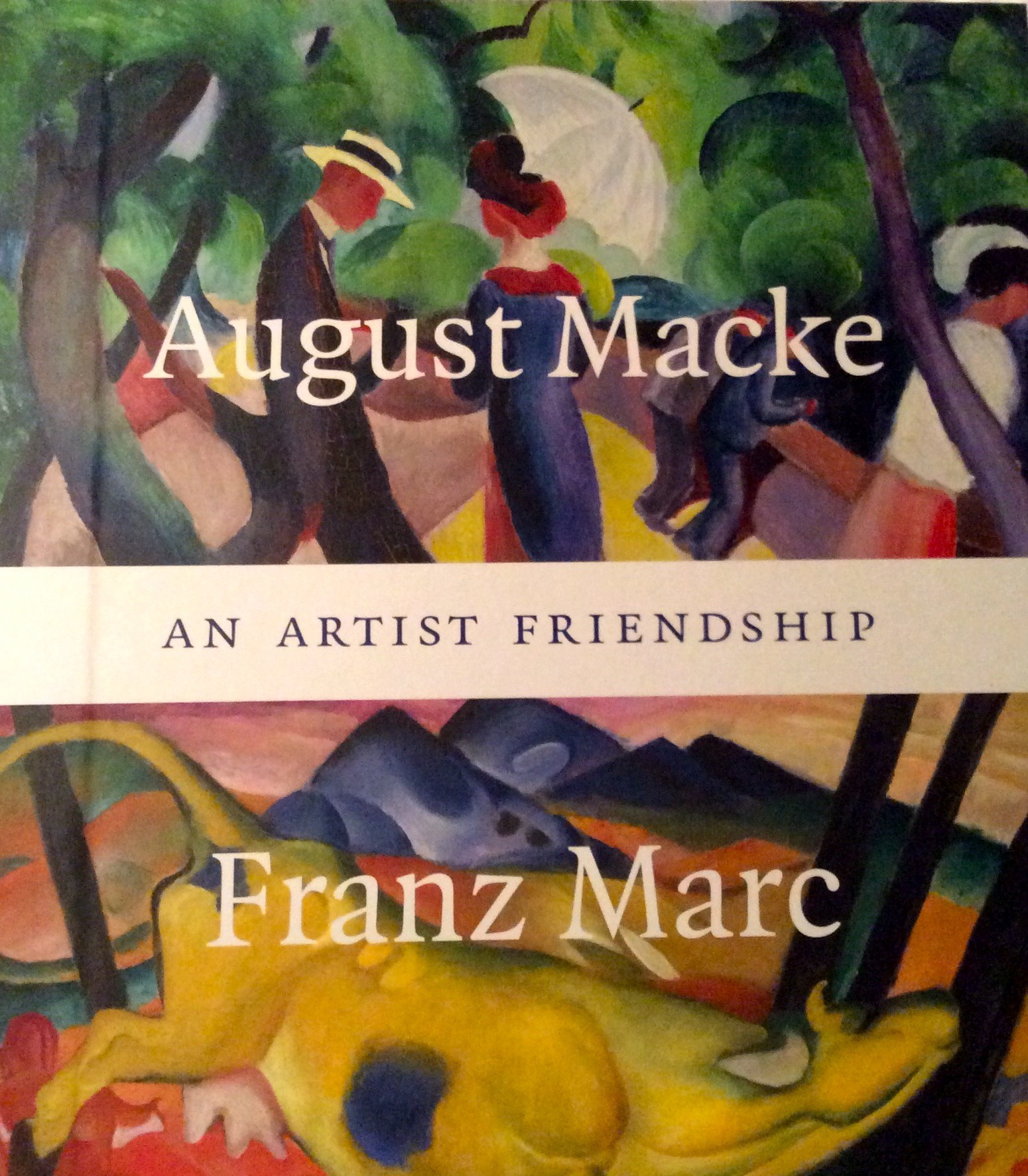

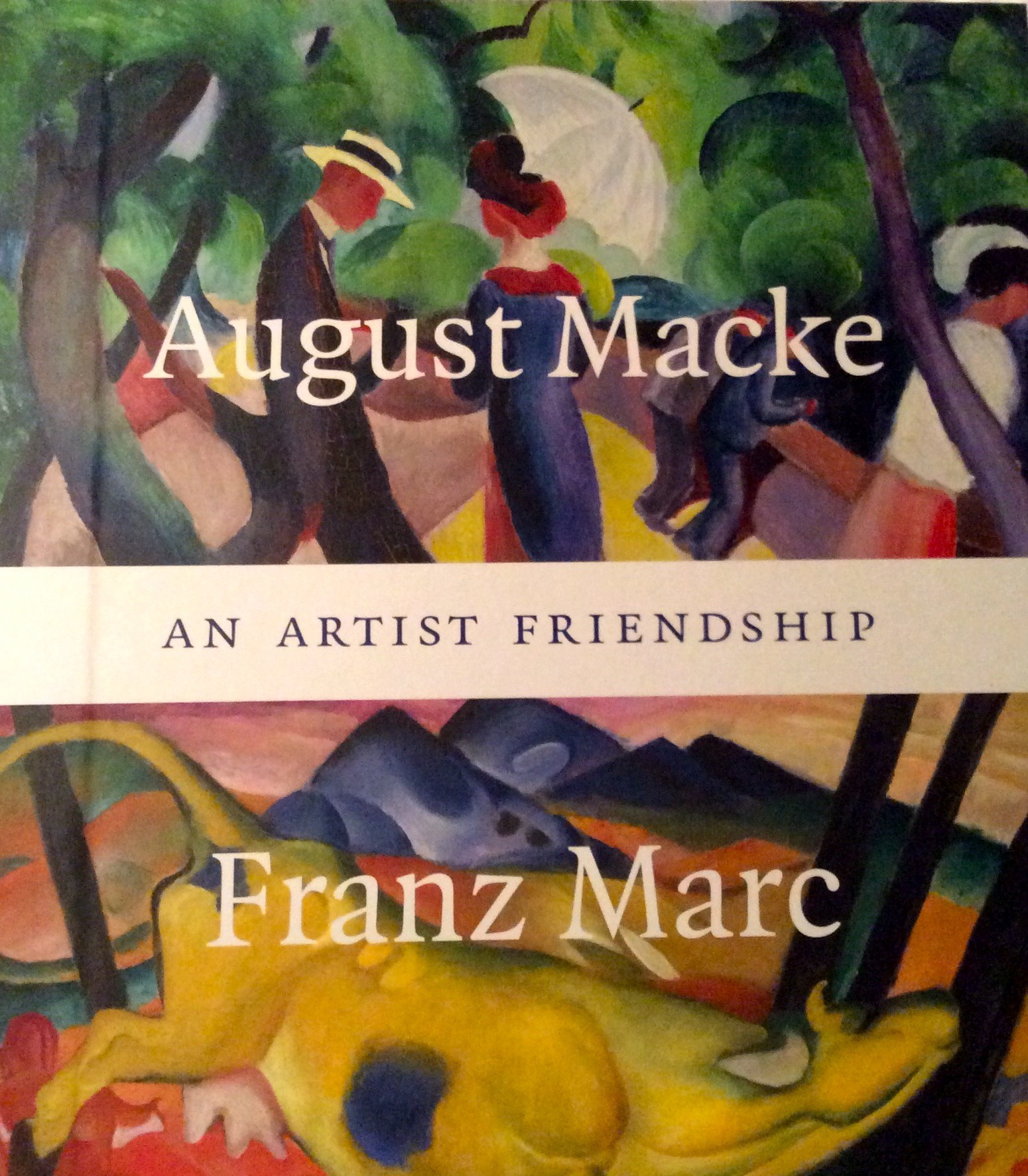

Book Review: August Macke and Franz Marc: An Artist Friendship

Catalog of an exhibition held at the Kunstmuseum Bonn, 25 September 2014 – 4 January 2015; and at the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau, Munich, 28 January – 3 May 2015; 359 pages with many color illustrations and black and white archival photographs.

I recently began doing some book reviews for Museum Bookstore, an online repository of catalogues and other printed material generated on behalf of museum and gallery exhibitions. My first review is of my favorite book of 2014-2015, the outstanding catalogue presented by the Lenbachhaus and Kunstmuseum Bonn in support of August Macke und Franz Marc: eine Künstlerfreundschaft. Please support this very worthy independent bookstore effort by checking out the companion text on the site.

§ § §

Published on 26 September 1914 to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the death of August Macke as well as the launch of the ambitious cooperative retrospective of Macke’s and Franz Marc’s overlapping oeuvres, the exhibition catalogue August Macke and Franz Marc: An Artist Friendship (August Macke und Franz Marc: eine Künstlerfreundschaft is its twin in the original German from which the English version has been translated) is, perhaps not surprisingly, a tour-de-force of editing and research. What is unexpected is that the editors, longtime Lenbachhaus Blaue Reiter curator Annegret Hoberg and Volker Adolphs of Kunstmuseum Bonn, along with a smartly-assembled team of university- and museum-based German art historians, bring to bear not just a wealth of knowledge but so much compassion to these essays, confronting directly the loss and sadness we naturally feel over the too-short lives of Marc and Macke. Macke, the extroverted Rhinelander, was killed in Champagne, France, at 27, while Marc, the contemplative Bavarian, died aged 36 at Verdun in the spring of 1916.

Despite their frank sentimentality, the catalogue’s chapters and essays are impeccably scholarly. Hoberg’s “August Macke and Franz Marc / Ideas for a Renewal of Painting” and Adolphs’ “Seeing the World and Seeing Through the World / Nature in the Work of August Macke and Franz Marc” are classic art historiography based in peerless analysis. Hoberg focuses on the milieu of the international avant-garde that encouraged Marc and Macke to not only follow the careers of but become personally acquainted with the Parisian Orphist Robert Delaunay and the Italian Futurist Umberto Boccioni. While Marc’s primary subjects directly encompass animals and the pastoral, albeit reframed through a unique pantheistic realism, Macke, who often painted urban scenes, has a less direct relationship to “nature,” which Adolphs teases out, particularly in comparison to Marc.

Despite their frank sentimentality, the catalogue’s chapters and essays are impeccably scholarly. Hoberg’s “August Macke and Franz Marc / Ideas for a Renewal of Painting” and Adolphs’ “Seeing the World and Seeing Through the World / Nature in the Work of August Macke and Franz Marc” are classic art historiography based in peerless analysis. Hoberg focuses on the milieu of the international avant-garde that encouraged Marc and Macke to not only follow the careers of but become personally acquainted with the Parisian Orphist Robert Delaunay and the Italian Futurist Umberto Boccioni. While Marc’s primary subjects directly encompass animals and the pastoral, albeit reframed through a unique pantheistic realism, Macke, who often painted urban scenes, has a less direct relationship to “nature,” which Adolphs teases out, particularly in comparison to Marc.

(more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 27 Oct 2014 | Animals, Animals in Art, German Expressionism / Modernism

The Cry of Nature: Art and the Making of Animal Rights

I got a note from the nice people at Sehepunkte about the review of Stephen Eisenman’s The Cry of Nature I wrote (which is posted on Sehepunkte’s website):

“Sofern Sie über eine eigene Präsentation im Internet verfügen, würden wir uns freuen, wenn Sie dort Ihre Rezension und unser Journal verlinken würden. Hierfür können Sie gerne auch eines unserer Logos … verwenden…”

…so of course, OK! I really like Sehepunkte and am working on some more stuff for them too.

So here the logo: 🙂

Now a few months after reading it, I should report that this book has had a nice slow burn and even though this is a very positive review I think I would rate it even more highly now, particularly as a teaching text as it covers a broad subject area still with clarity and depth in each chapter. I was able to use Eisenman’s section on the hunting practice of indigenous peoples, for example, as a point of reference in a recent seminar I gave for the Bioethics Centre at the university and in reference to a discussion about the dolphin massacre in Taiji, Japan. (To support my argument against hunting and hunters I mean: Don’t get me wrong; there’s no place for humans who hunt in any universe, and people trying to be “open minded” about hunting are without fail patronizing, paternalistic, and dead inside.)

Anyway, this is an excellent book and here is the review:

(Stephen F. Eisenman: The Cry of Nature. Art and the Making of Animal Rights, London: Reaktion Books 2013, ISBN 978-1-78023-195-2).

Art historical texts, and especially single-authored volumes, should be judged in great measure by how well they fulfill their expressed ambitions. By this rule The Cry of Nature. Art and the Making of Animal Rights, whose central objective is to provide an intellectual and informational resource for readers interested in the intersection of the animal studies and the making of art, and a platform for scholars to reflect on provocative subjects suggested by the twining of these two themes, must be deemed a success.

Each of its chapters contributes to author Stephen F. Eisenman’s goal of addressing and evaluating important issues pertaining to the contemporary discussion of animal rights and the movement’s connection to art and ideas originating in the 18th century as well as, to some extent, before. Organized into five chapters and a strong introduction and conclusion, plus a recommended reading list of some of the foundational volumes of the relatively new discipline of animal studies, the book surveys not only images but historicizing texts and makes a strong claim that something like an animal rights movement has existed since antiquity, springing into cohesion in the 1700s, with artists making and using images as persuasion and propaganda.

The pleasure derived from reading this book lies partially in the richness of Eisenman’s detailed, personal, and confident descriptions of the lives and emotions of real animals, making his prose eminently accessible. Readers will be compelled by the forcefulness of local histories about, for example, a majestic African elephant photographed in a moment of perfect stillness at a watering hole in 2007 who is killed by poachers in 2009, and delighted by anecdotes about Echo, the author’s dog, who learns to stage pratfalls and tumbles in order to make Eisenman laugh. These stories are integrated meticulously within more formal discussions of images – some well-studied, including Rosa Bonheur’s The Horse Fair (1853) and Jean-Baptiste Oudry’s A Hare and a Leg of Lamb (1742), some less famous – such as Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri’s 1975 painting Eagle Dreaming – which are produced about, and in mindfulness of, the animal.

The book begins with a background chapter defining “What is an Animal?” in terms of societal mores and biological evidence about the commonalities and differences amid living creatures, centering on the ability of animals to communicate, to experience emotions, and to feel pain. This chapter includes pleasantly unexpected exemplars, such as Simon Tookoome’s 1979 linocut I Am Always Thinking of Animals, as it stakes out the moral and practical discussions around how we define language and consciousness.

The chapters “Animals into Meat” and “Counter Revolution” dwell on images of the corpses of animals, shown as food, prey, and sacrificial stand-in for the human figure and body. While the recurring motif of the flayed ox in paintings by Gustave Caillebotte and Rembrandt may arouse as much distancing disgust as identification, Eisenman’s delicate examination of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s The Ray (1728) makes persuasive on the page that these artists intended to convey their beliefs in the existence of the souls and consciousness of animals, and commensurately, the dismal mortality of humans, on their canvases. (more…)

by Jean Marie Carey | 23 Mar 2014 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Dogs!, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

Franz Marc’s family home in the München suburb of Pasing.

I’ve written a little bit about (we’re saving our full repertoire for our even-bigger-screen reveal) the accidental hobby of my creative partner and myself, a sort of reverse geocaching + film. Basically we found out we like to research the addresses of art-historical places and find the spot on the earth where they once stood. In most of these cases, such as the pop-up gallery in Berlin search which ended up being recorded during a blizzard, or the colorful studio here in München destroyed in the war, we had city records and things like invitations to or posters for exhibits to go on, and it was possible to figure out, even where addresses had changed or buildings had been demolished, where they once stood. Sometimes we were able to use GPS coordinates, tagging our own maps as we went along, and sometimes we just used a compass, building keystones, and asking questions. Most of these excursions took a couple days of research and a one-shot hike.

Franz Marc’s family house in the München suburb of Pasing turned out to be our biggest challenge, though, and somewhat unexpectedly since Pasing was never destroyed and a lot of the old buildings have been preserved. However, perhaps not surprisingly, neither were Sophie and Wilhelm Marc, the parents of Franz, nor Paul, Franz’s brother, either very good with managing money nor with keeping records. Thus as it turns out the Marcs owned the house through a chain of convoluted machinations, so the normally very useful city and state records were not helpful. We assembled our clues – fragments of notes and letters mostly, and importantly, photographs showing the house and the yard – and set off to Pasing with only a couple of bottles of water because “how big can Pasing be?”.

Well, Pasing is not that big, but, never underestimate the amount of confusion Franz Marc can cause. On our first journey (like, on the Straßenbahn Linie 19 so not that far) we walked around the neighborhood with the most Altbauten – nothing. The second day we knew to bring some snacks, but, still, after many hours – nothing. We were getting a bit anxious time-wise, and looked over all our notes again. I kept going back to the photographs, which showed very clear views of the property including which way the shadows were falling, and, since they photos were clearly taken in summer, and then in winter, you could see which way the house itself faced. We decided on the third trip to just be more playful and counterintuitively left everything at home but the camera, and getting off the tram just walked in a direction that seemed, for lack of a better way to describe, enticing and pleasant.

Not even half an hour into the walk, we turned a corner, and there it was. The other times we had been going completely in the wrong directions, by the way. Even if I didn’t know from the photographs, I would have just known, I think, that this was a place the Marc family would have lived. It’s a comfortably large enough home, but kind of secluded, even though it’s on city block, with many trees that were saplings in the photographs, a sort of open gazebo, and many eaves and places for birds to live. It definitely had an aura and I was very happy to have found the place – it made me feel very light at heart – and happy that the Marcs had lived there. Sophie Marc stayed on at the house after Wilhelm Marc died in 1907 until she went to stay with Maria Marc later in 1914 (yes, Sophie Marc outlived Franz by just a few months).

Unfortunately, as you can see from the photos, the home is abandoned and in desperate need of some repairs. It’s probably not habitable the way it is now. I dearly hope someone will lovingly restore this historic treasure. If that person is you, please write to me and I will send you the address!

Once my heart had turned to being interested in “recovered biography” I realized how important it is to actually physically experience places and things important in the life of Franz Marc. It’s incredible to me that in a place as self-consciously “historic” as Bayern so many things are falling away. In 2013, the Goltz book store closed its physical location on the Türkenstraße, which should really have been outlawed or something. We did make some documentation of that location, too, though. But that is another story.

UPDATE: May 2015

In some recent research I was doing about some other property records and dates of births and things, I ran across an interesting fact: Around 1885-1900, Annette von Eckardt and her family, which then would have included her baby daughter Helene and husband Richard Simon, a professor at Ludwig-Maximilians Universität, lived in Pasing. By this time Richard Simon would’ve known Paul Marc, Franz Marc’s brother who also taught at the university, and who still lived with the family in Pasing, too. I’m writing something for publication about these interconnected relationships for soon, so…watch this space. The implications are interesting, and a little disturbing, too, but my intuition has been givine me this message for a long time…

by Jean Marie Carey | 8 Feb 2014 | Animals, Animals in Art, Art History, Franz Marc, German Expressionism / Modernism, LÖL, Re-Enactments© and MashUps

Tierschicksale, 1914, Franz Marc

Was kann man thun zur Seligkeit als alles aufgeben und fliehen? als einen Strich ziehen zwischen dem Gestern und dem Heute? – Franz Marc, February 1914, from the intended introduction to the second edition of the Blaue Reiter Almanac. First printed in Der Blaue Reiter. Dokumentarische Neuausgabe by Klaus Lankheit. München, 1965, p. 325.

One of the most frequently cited articles about Franz Marc in popular literature is Frederick S. Levine’s “The Iconography of Franz Marc’s Fate of the Animals” from a 1976 issue of The Art Bulletin, and, subsequently, a short book on the same subject. Apparently there are some issues with the accuracy of the translations presented in both. What’s interesting to me is the creative idea Levine had to analyze Marc’s enormous 1913 painting Tierschicksale (mysteriously residing in the Kunstmuseum Basel) as an expression of Ragnarök, the apocalypse of Norse mythology. My opinion is that despite being generally familiar with the Eddas and with Der Ring des Nibelungen Marc wasn’t that interested in these sagas and didn’t consider them as particularly German.

A few years ago Andreas Hüneke, researching at the Lenbachhaus, discovered that the inscription on the back of the painting, „Und alles Sein ist flammend Leid“ is from a volume of the Buddhist Dhammapada of the Pali Canon of Buddha Siddhartha Gautama given to Marc by Annette von Eckardt. So it doesn’t seem to refer to Ragnarök directly as Levine (not having the benefit of Hüneke’s recent work) asserts. It seems more likely that Marc was very distressed, in the summer of 1913 when he made Tierschicksale, about von Eckardt’s move away from Munich to Sarajevo. It explains a little bit about why, upon seeing the painting again a few years later, Marc says he doesn’t even remember creating it and ascribes its meaning to the more external conflagration at hand.

In any case, Levine was not discouraged by his translating experience and went on to the faculty at Palomar College in California and also spent a lot of time studying and teaching at the University of Tasmania in Hobart.

Today, on Marc’s birthday, with so many animals imperiled, Tierschicksale doesn’t really need any overdetermining; it would be very tempting to just turn and flee, if only there was somewhere to go.

by Jean Marie Carey | 13 Sep 2013 | Animals in Art, Franz Marc, Stuff Found in Library Books

When I was little I was lucky to find my way very young to The Black Stallion books by Walter Farley. I read every single book (they appeared every other year or so from 1941 to 1983; the original book was made by  into a stunning film of the same name) many times and like the Jim Kjelgaard dog books (Snow Dog, Big Red) I still read them once in a while. As a child I had Breyer horses and Barkies dogs and the scale of the models was compatible enough that I created an early kind of fan fiction diorama series in which the dogs from the Kjelgaard books met the horses from the Farley books.

into a stunning film of the same name) many times and like the Jim Kjelgaard dog books (Snow Dog, Big Red) I still read them once in a while. As a child I had Breyer horses and Barkies dogs and the scale of the models was compatible enough that I created an early kind of fan fiction diorama series in which the dogs from the Kjelgaard books met the horses from the Farley books.

Of the horses, I actually preferred The Island Stallion, Flame, and Black Minx, the Black’s (Shêtân) daughter. Also some of the “supporting” horse characters, particularly Wintertime and Sunraider. Of course Eclipse and the Piebald were fantastic villains. Unlike Kjelgaard, who told his stories from the perspective of the animals alone, Farley mixed the narratives voices between humans and horses mostly to good effect. Generally both these series of books are underrated and understudied; they are every bit as elegant and meaningful as Call of the Wild without the violence and free from the burden of having to explain the stereotypes of the time; so they remain free for children to enjoy today.

I was thinking about the Black Minx on and off for the past few weeks and even had a dream about the race with Eclipse that is the set piece of The Black Stallion’s Courage.

The Black Minx and Eclipse… Black Minx is the one horse whose speed potential we never really learn. Only “the boy”, Alec Ramsay, can inspire obedience in the headstrong filly. She was a poky frontrunner…she would get out in front of the other horses in every race, put lengths and lengths of distance between herself and the pack, and then…begin daydreaming until she wandered across the finish, albeit still the winner. She is also a bit romantic in other ways, falling in love with her colt rival Wintertime (who like Flame is a solid chestnut) and always wanting to play around with the other horses and guide ponies. Alec decides to “make” Black Minx more competitive by running her with Eclipse (who is dark bay), the wonder colt she bests in the Kentucky Derby but who rapidly thereafter matures into both a magnificent athlete and a terror, speedier (for a spell) even than the Black and cruel, toying with and breaking the spirits of his rivals.

But this plan backfires. The Black Minx bitterly resents having her dedication tested and the forced competition with Eclipse, whom she loathes. She never trusts Alec again. Moreover in these trials she is faster; Black Minx knows all along that even though Eclipse is very fast, she is too far ahead – all she has to do is hold her lead, which she does. Eclipse is bitter about Black Minx’s ease. Finally, in the Belmont Stakes, when all the horses (except the Black) race, Black Minx protests. Wintertime can’t keep the pace Black Minx and Eclipse set, so Black Minx simply slows down and keeps pace with Wintertime. Eclipse surges across the finish line breaking a track and world record. But as Alec races to Black Minx to make sure everything is OK, Eclipse realizes that Alec loved her best no matter what, win or lose. So for Alec and Eclipse, this is a sad story in terms of people-horse relations. For Black Minx, following her refusal to compete, she is retired, as is Wintertime, and they spend the rest of their days together. (In the very last books of the series, Wintertime and Black Minx have a daughter who is also unruly, Black Pepper.)

Tim Farley, Walter Farley’s son, maintains a Black Stallion Website that has a very fun forum, a lot of beautiful images of horses, naturally, stills and clips from the movies, and a real treasure – the vintage covers from the first editions of each of the books.

Despite their frank sentimentality, the catalogue’s chapters and essays are impeccably scholarly. Hoberg’s “August Macke and Franz Marc / Ideas for a Renewal of Painting” and Adolphs’ “Seeing the World and Seeing Through the World / Nature in the Work of August Macke and Franz Marc” are classic art historiography based in peerless analysis. Hoberg focuses on the milieu of the international avant-garde that encouraged Marc and Macke to not only follow the careers of but become personally acquainted with the Parisian Orphist Robert Delaunay and the Italian Futurist Umberto Boccioni. While Marc’s primary subjects directly encompass animals and the pastoral, albeit reframed through a unique pantheistic realism, Macke, who often painted urban scenes, has a less direct relationship to “nature,” which Adolphs teases out, particularly in comparison to Marc.

Despite their frank sentimentality, the catalogue’s chapters and essays are impeccably scholarly. Hoberg’s “August Macke and Franz Marc / Ideas for a Renewal of Painting” and Adolphs’ “Seeing the World and Seeing Through the World / Nature in the Work of August Macke and Franz Marc” are classic art historiography based in peerless analysis. Hoberg focuses on the milieu of the international avant-garde that encouraged Marc and Macke to not only follow the careers of but become personally acquainted with the Parisian Orphist Robert Delaunay and the Italian Futurist Umberto Boccioni. While Marc’s primary subjects directly encompass animals and the pastoral, albeit reframed through a unique pantheistic realism, Macke, who often painted urban scenes, has a less direct relationship to “nature,” which Adolphs teases out, particularly in comparison to Marc.