One of the paradoxes that has emerged from documenta 14 is that many of its spectacular installations make very simple statements about global consumerism using enormous material expenditures. In fact it can be difficult to see past the pyramids, windmills, and tents erected to comment on issues such as migration and the market-possessed-body – elaborate efforts to illustrate political generalities – to documenta’s truer theme, an attempt by curator Adam Szymczyk to assail, or at least supplement, canonical art history with work by indigenous and overlooked artists.

iQhiya, Monday, 2017, Performance und Installation, Ehemaliger unterirdischer Bahnhof (KulturBahnhof), Kassel, documenta 14, Foto: Fred Dott

But the contemporary art fair world floats above scholarship on a bubble of self-satisfaction. The documenta participants who are the big draws – Mona Hatoum and Pierre Huyghe for example – aren’t worried about posterity. So what was meant to be exposure becomes competition for a footnote. Some of this lesser-known work also really struggles when removed from its local context. Poor facture and inappropriate plinths meant as faux–naïf comes across as a weird form of doubled sociological good intentions gone awry, and, amid Kassel’s half-hearted Brutalist buildings, calls to mind Bernd and Hilla Becher’s photographs of Bavarians dressed as Native Americans. In this respect, perhaps it was afterall an important achievement, and more consistent with Szymczyk’s goal, to move the most of documenta to Athens.

One excellent work, shown above, is iQhiya’s Monday (2017), which unfortunately was performed only once on 13 June. Staged in Kassel’s “little” Bahnhof, the spoken, moved, video, books, saws, pens, needles cloth, and film endurance piece used an eight-hour projection loop of Sarafina! (1992) to examine the “hidden curriculum” experience of black, South African women college students. Mimicking the rhythm of a real school day, naturally people wandered in and out. The coming and goings of the Eurobahn and Regio trains moving through the station plinked the hour glass and also made a rumbling vibration that was unsettling and comforting at the same time. I’m not sure if the reference to Pascale Marthine Tayou’s Human Being @Work (2009) was intentional or ephemeral coincidence, but the eleven-member iQhiya troupe made use of sound and light in a similar way as Tayou’s (also very successful) occupation of the Biennale di Venezia’s Arsenale – only with real trains.

Olu Oguibe, Das Fremdlinge und Flüchtlinge Monument, 2017, Beton, Königsplatz, Kassel, documenta 14, Foto: Jean Marie Carey

The week of 19 June, a 16-metre-tall obelisk made of concrete was unveiled on Kassel’s central Königsplatz, on an axis between the Straßenbahn tracks, newsstand, and Starbucks. The early summer sun illuminated a facing of Arabic characters, the artist inspecting each side, nodding in affirmation. On the other sides the same message is written in Turkish, English, and German: “I was a stranger and you took me in,” a quotation from Matthew’s message of hospitality, a tenet of the New Testament. The obelisk is a work of art from Olu Oguibe, a native of Eastern Nigeria, who has lived for a long time in the United States. It is hard to tell if the words are intended as a compliment or a criticism (though I suspect the latter), but they have a comical effect in the strange town in this corner or Nordhessen and its mumbly, grumpy morning Fußgängerweg commuters – whom include many Somalian and Syrian now-residents – 15,000 in Kassel since 2015 – and people from every other place, including myself.

Oguibe chose the obelisk to bear these words, as its form is a reminder that the Romans, then the other European colonizers, bore such monuments from North Africa in the time of Christ and later as a sign of their empire-ship. Before settling at the University of Connecticut and his various other curating and art making posts, Oguibe once – at the end of the last century – held the Stuart Golding Endowed Chair in African Art at the University of South Florida. So it was both surprising, and completely expected, to see him in Kassel.

Beau Dick, Installationsansicht, documenta Halle, Kassel, documenta 14, Foto: Roman März

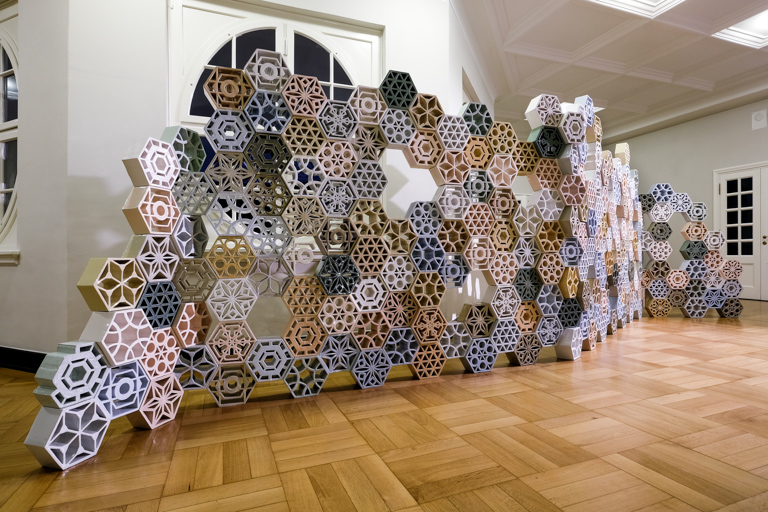

Nevin Aladağ, Jali, 2017, glasierte Keramik, Installationsansicht, Hessisches Landesmuseum, Kassel, documenta 14, Foto: Michael Nast

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts