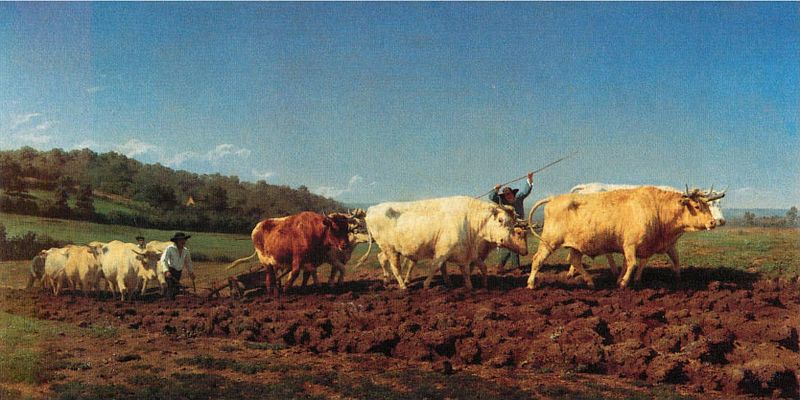

Rosa Bonheur – Labourage nivernais.

If 19th century French painter Rosa Bonheur believed in reincarnation, she would surely have chosen to return to life not as one of the regal lions or leggy gazelles she shared her Bordeaux estate with, but as a sturdy, common barnyard bull. The slyly successful painter had great affection for domestic animals, and enjoyed her greatest artistic success depicting them.

Bonheur was especially adept at imbuing cattle with nobility without giving them airs of humanity.

Though best known for The Horse Fair (1853), a canvas from a few years later in her career, Labourages Nivernais, completed in 1850, is actually a less derivative, more personal, visually individualistic image of Bonheur’s favorite creatures. Nivernais also marks the beginning of a period of commercial and public success for Bonheur, a good fortune enjoyed by few women artists then as now.

At first glance, Nivernais seems a relatively innocuous, though beautifully rendered, ode to agrarian life, and there is nothing “incorrect” with that interpretation. However, Nivernais offers much more to viewers who, like the team of oxen shown, take the time to turn over the well-trodden earth.

Rosa Bonheur, was born in Bordeaux, France on March 16, 1822, the eldest child of Sophie Marquis and Raimond Oscar-Marie Bonheur. The couple called the baby Marie Rosalie, but she almost immediately came to be known as Rosa.

Her father, himself a painter and philosopher, and artists with whom he was friends captured many images of the youthful RB.

Her father shows RB the infant idolized as a cherub in a crib in a painting in 1823. By the time Raimond Bonheur captured Rosa at Four, the child had the set jaw, solemn gaze, erect posture and short tousled hair that would identify her for the rest of her life.

One alleged portrait of RB, showing a square-jawed, serious child in a brimmed hat with feather trim, was painted by Jean Baptiste Camille Corot. After RB’s death, though, her companion Anna Klumpke, came forward to say that she thought the sitter for the portrait was instead a male. Such confusion regarding appearance and gender shadowed RB all her life.

By the time RB was five years old, she had two younger brothers, Auguste and Isidore. Cultured and socially and intellectually ambitious but poor, both parents worked, Sophie Bonheur giving piano lessons and Raimond Bonheur experimenting with various schools of art and religious thought.

RB quickly made her lifelong love for animals evident, playing from the time she could walk in nearby horse stables, with country dogs and cats, and in pastures where sheep and cows lived.

Sophie Bonheur encouraged both her daughter’s affection for animals and the child’s abilities in arts. The toddler designed and cut out paper animals, learned her ABCs by associating each character with a certain creature, and began fledgling studies of animals in charcoal, paint and clay.

Raimond Bonheur moved back and forth between Bordeaux and Paris during the late 1830s, leaving Sophie Bonheur to tend to what was now a family of four children, a farm, and two elderly parents. Sophie Bonheur died in 1830, probably of pneumonia, but RB undoubtedly believed that the exhaustion of domestic drudgery had taken a fatal toll on her creative, talented and sensitive mother.

Though as an adult, she would strive to surround herself in equanimity and tranquillity, at age 11, RB found her life in upheaval. Following her mother’s death, RB was sent to live with a dressmaker whom she was apprenticed to, while her brothers went to a boarding school where Raimond Bonheur gave lessons to pay their tuition.

RB preferred the woodshop behind the dressmaker’s salon and soon found herself at a boarding school as well, one for wealthy children on the outskirts of Paris. The girl who was used to romping with animals did not fit in, and again, she was dismissed.

This time, though, Raimond Bonheur allowed the girl to come live with him and study in his studio. He developed for her a curriculum of drawing landscapes and animals, and sent her to the Louvre to make faithful copies of the paintings there. Concerned over her lack of formal classroom education, Raimond Bonheur encouraged RB to read about French history and literature in the evenings.

In 1836, Raimond Bonheur was commissioned to paint the portrait of Nathalie Micas, the sickly 12-year-old daughter of a well-to-do Paris family. RB became close to the family and particularly intimate with Nathalie.

Eventually, Raimond Bonheur (who changed the spelling of his name to “Raymond” in the 1840s) remarried, and Auguste, Isidore and Juliette, the youngest child, joined the family in Paris. They moved to a large apartment on Rue Rumford, still in the city but close enough to fields and farms for RB to continue to enjoy them. Inside the apartment house, the Bonheurs kept ducks, rabbits, quail, goats and sheep.

Rosa Bonheur with one of her bulls

RB had become an accomplished painter of landscapes and animals, and, at the age of 19, she entered a charming small canvas, Rabbits Nibbling Carrots, in the Salon of 1841, as well as some of her small bronzes of sheep, rabbits and goats. To the relief of her father, RB was ignored, not derided, for her entries by the critics, which the family considered something of a silent victory. Though RB would come up with her own solutions for dealing with her place, time and gender, women were usually not recognized or welcome in the Byzantine hierarchy of Salon politics.

RB sold some of her bronzes, and became an admirer of the work of Theodore Gericault and Eugene Delacroix. When she learned that Gericault had studied cattle at the slaughterhouses, she followed suit.

About this time, RB began dressing for “work” as a man. She even obtained a “permission de travestissment” from the Paris police so she could wear men’s garb for her drawing sessions at the slaughterhouse, and, later, in the fields. RB never acknowledged her manner of dress as a statement of feminism or allowed that it served any other than a utilitarian purpose.

Far from being repulsed by the iconoclastic tomboy, though, French painting academics embraced the woman and her tenderly rendered portraits and sculptures of animals.

RB’s was awarded a sort of “honorable mention” prize in the Salon of 1845, and her work began to sell. In 1848 her painting Cows and Bulls of the Cantal received the Salon’s gold medal.

By 1853, RB was a French celebrity, an established and successful painter, and a guest of the Queen of England. Reproduction sales of the enormously popular Horse Fair were steady, and RB was able to purchase a large chateau where she lived first with Micas, who eventually succumbed to the poor health that had dogged her for years, later with another companion, Anna Klumpke.

Klumpke, much younger than RB, was an American painter born in San Francisco and educated in Paris. The affection RB had lavished on Micas was transferred to Klumpke, much to the Klumpke and Bonheur families’ distress. RB wrote a letter to Klumpke’s mother stating that the pair wished to “associate our lives.” Quite presciently, Bonheur had come up with the idea of “adopting” her same-sex partner, protecting reputations as well as Klumpke’s financial well-being.

The chateau was home to a large number of domestic and rescued wild animals. RB even traveled to the United States, when, in 1889, she was invited to paint a portrait of “Buffalo Bill” William Cody.

Yet RB remained, in retrospect most appropriately, linked in image with the bovine rather than the equine, and Ploughing in the Nivernais stands as her breakthrough work.

Commissioned in 1848 by the French Ministry of Agriculture to create a painting on the subject of ploughing, RB made the working cattle, rather than the farmers, her subject.

The painting makes majestic, almost mythical, subjects of a team of bulls bathed in a sunny glow, their short, thick coats a burnished golden, bay and blond, and they are followed by another team of six bulls. The fact that the animals are harnessed and yoked seems almost incidental. Compared to the cows, the human subjects are dwarfed and insignificant, their faces averted or indistinguishable.

Diagonal lines are an important formal element of Nivernais. The oxen team looms into the foreground from the left at an angle that carves a wedge into the landscape aspects of the canvas. The sky at the right, therefore, opens wide over the back of the oxen and over the heads of their human attendants.

This gives the already forceful image an added push, as if the atmosphere is compressing behind the ploughing team and pushing it ahead. The furrowed land, meanwhile, is a completely flat horizontal plane, emphasizing its dormant but fecund state.

Given Bonheur’s enthusiasm for the subject, Nivernais features an unusual lighting scheme, one that is curiously flat and direct. Rather than showing the ploughmen out and at it at dawn, bathed in pinkish hues, or returning from the fields before an orange sunset, the sun is directly over head in a harsh, cloudless sky not particularly mindful of the coming warm weather.

The cattle, meanwhile, stride rather than trudge over the land they are pulling the plough over, heads tossing, eyes towards the viewer. There are hills at their rear, a cloudless blue sky over their heads, and in front of them, a plot of cultivated land, probably their home, which their shadows almost touch at the right border of the painting.

In The Fall of Icarus, Pieter Brueghel uses ploughing to comment on the pragmatic farmer too bound to the earth to react with astonishment to the sight of a boy falling from the sky. Though Bonheur’s take on ploughing is more literal, her portrayal of cattle transcends a romantic genre scene. Nivernais shares another curious similarity to the Brueghel painting: several versions of it exist.

After completing the original Ploughing in the Nivernais

The big one with the cows.

for the French government in1849, RB made a signed copy of the painting, dated 1850, which was sold to a private collector for 4000FF, half of which RB gave to her brother, Auguste, for his collaboration in the reproduction. Ruefully, RB noted that she received 1000FF more for the second version than she had for the original.

The 1976 Theodore Stanton book Reminiscences of Rosa Bonheur is a collection of correspondence between RB and members of her family and friends. She seems to have had little interest in the upheaval in European politics at the time, and despite her extensive discourse on many subjects, she deconstructed her own artwork and feelings about it very little.

RB did, however, talk about the creation of Ploughing in the Nivernais from a technical standpoint, and also credited some of the inspiration for the painting’s composition to George Sand. Sand had written in The Devil’s Pond, “…but what caught my attention was a truly beautiful sight, a noble subject for a painter…a handsome young man was driving a magnificent team of oxen.” (Typical of her disingenuous nature, Bonheur made no reference to Sand’s famous masculine attire and mannerisms.)

In versions of Nivernais, and in textbooks and books about Bonheur, the precise color and texture of the canvas are difficult to assess. Thus, seeing the painting at the Ringling Museum is a revelation.

To convey the mass of the cattle, Bonheur very much relies on her academic training and knowledge of anatomy. Rather than using thick, chunky daubs of paint to indicate the coarseness of the bulls’ coats, Bonheur employs fine, small brush strokes of even depth to pick out each curl and tuft.

Reproductions of Nivernais often seem to give a weirdly acidic tone to the yellows and blues in the color scheme, almost like the work of Ingres. However, “in person,” the colors are much warmer, the sky a true Aegean blue, the cattle ruddy and the earth shot through with veins of terra cotta and sienna.

Affectionately described by a docent at the Ringling Museum as “that big one with the cows,” Nivernais is an impressive eight feet in length. Bonheur liked to use large canvasses for her animal subjects. Some of her biographers suggest that Bonheur enjoyed portraying herself as a dainty woman grappling with an enormous space, but another interpretation would be that Bonheur, who was quite pragmatic in many ways, simply thought that big animals should be shown in relatively large dimensions.

When the portraitist Edouard-Louis Dubufe painted RB in 1857, she was dissatisfied with the rendering, which she thought boring. RB adjusted the image herself, brushing out the desk Dubufe had shown her leaning against, replacing the furniture with the image of one of her favorite bulls, a ruddy fellow with a white forelock.

During 1899, the last year of her life, RB allowed Klumpke to make a painting of Bonheur sitting in her studio.

RB’s white hair illuminates her patient, aristocratic face, youthful and softened by her love and contact with animals. She wears an ochre cloak and the rosettes of her Legion of Honor medals, and is shown beside her final canvas, La Foulaison, which she was unable to finish. That canvas hangs today at the Chateau de By.

Bibliography

Stanton, Theodore. 1976. Reminiscences of Rosa Bonheur New York, NY.: Hacker Art Books

Turner, Robin Montana. 1991. Rosa Bonheur Boston, MA.: Little, Brown and Company

Ashton, Dore. 1981. Rosa Bonheur A Life and Legend New York, NY.: The Viking Press

Glueck, Grace 1997. Beyond Bonheur’s ‘Horse Fair’ The New York Times, 19 December 39(E)

Tuchman, Laura J. 1987. Exhibit reinforces notion that sexes are not equal The Orange County Register, 11 December 48(S)

Blume, Mary. 1997. The Rise and Fall of Rosa Bonheur The International Herald Tribune, 4 October 22(F)

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts